What is Kabuki? 8 Things You Need to Know About Kabuki Theater

by David McElhinney & Brooke Larsen | ART

© Lens on Japan / Creative Commons, Children’s Kabuki Theater in Nagahama

Kabuki is a world-renowned form of traditional Japanese performance art. Incorporating music, dance, and mime with elaborate costumes and sets, kabuki dramas depict tales derived from regional myths and history. Though internationally acclaimed today, its origins were humble and somewhat controversial. Many modern kabuki techniques and performers are directly descended from original methods and historical actors, leaving this artform largely unchanged for centuries. We’ll tell you all about the meaning, history, and methods behind this classical, complex and fascinating storytelling style.

Kabuki is one of the the three most famous Japanese traditional theater styles. Take a look at our essential guides to find out about Bunraku and Noh Theater.

1. What is Kabuki Theater?

2. How and When Did Kabuki Begin?

3. What are Kabuki Plays About?

4. Who Are the Most Famous Kabuki Actors and Playwrights?

5. What are the Key Elements of a Kabuki Performance?

6. Kabuki in Popular Culture

7. Where to See Kabuki In and Outside Japan?

8. Books to Learn More About Kabuki

1. What is Kabuki Theater?

Kabuki (歌舞伎) is made up of three kanji (Chinese characters): ka (歌) meaning sing, bu (舞) representing dance, and ki (伎) indicating skill. Literally, kabuki means the art of song and dance, but performances extend well beyond these two elements.

All told, Japanese kabuki is an outlandish visual spectacle which focuses more on looks than story. Production elements like costumes, lighting, props, and set design compliment performance aspects such as song and dance. All are presented in grandiose fashion to create a single, spectacular show.

2. How and When Did Kabuki Begin?

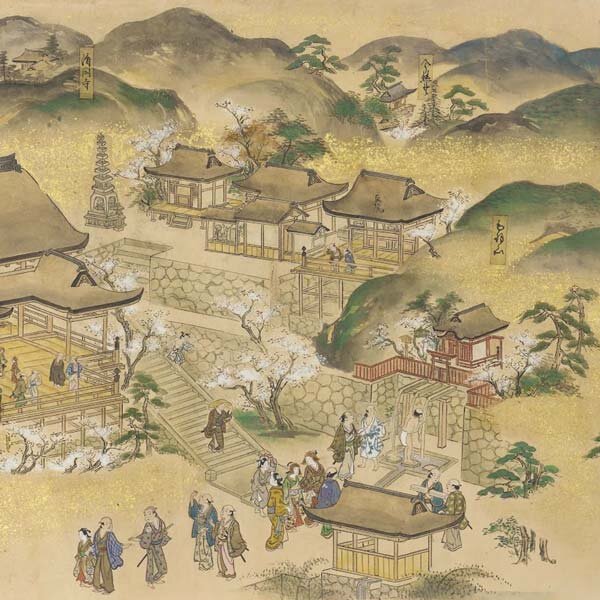

Ichimuraza Kabuki Theater, 1740s, by Masanobu Okumura

Today’s kabuki actors are all male, but the art was created by a woman. Izumo no Okuni was a Shinto priestess who began performing in the early 1600s at various locations around Kyoto, including at shrines and in the dry riverbed of the Kamo River. She formed an all-female troupe of local misfits and prostitutes, instructing them in theater, song, and dance. These women portrayed both male and female characters in comedic plays parodying everyday life. Known as onna-kabuki (onna means woman), the performances were witty and suggestive. This guerilla form of entertainment quickly became so immensely popular that rival troupes formed as far away as Tokyo (then called Edo) and Okuni herself was asked to perform for the Imperial Court.

Kabuki became common in red-light districts and also generally associated with prostitution, as performers sometimes offered their services to spectators. The ensuing moral panic led to the complete prohibition of women from performing in 1629. At first, young boys took over their roles, but they too were eligible for prostitution and also banned. Finally, adult men began performing, taking up the roles of both males and females as their predecessors had.

Yanone Kabuki Poster by Torii Kiyosada

Kabuki was initially seen as avant-garde, a bizarre niche form of entertainment for the common people. They were drawn to the early performance’s bold eccentricity and lewdness, and audiences were often rowdy. The original meaning of kabuki is speculated to be related to the verb kabuku (傾く) which can mean to behave oddly. It took decades to evolve into the popular, formalized artform it became.

The 18th century was the golden age of kabuki history. The structure of the performances was formalized, recurring character types established, and all stigma erased. However, the movements and visuals remained over the top. Since this era, kabuki has persisted as one of the greatest and most famous Japanese arts. It’s recognized as one of Japan's three major classical performance arts along with noh and bunraku, and is on the list of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

3. What are Kabuki Plays About?

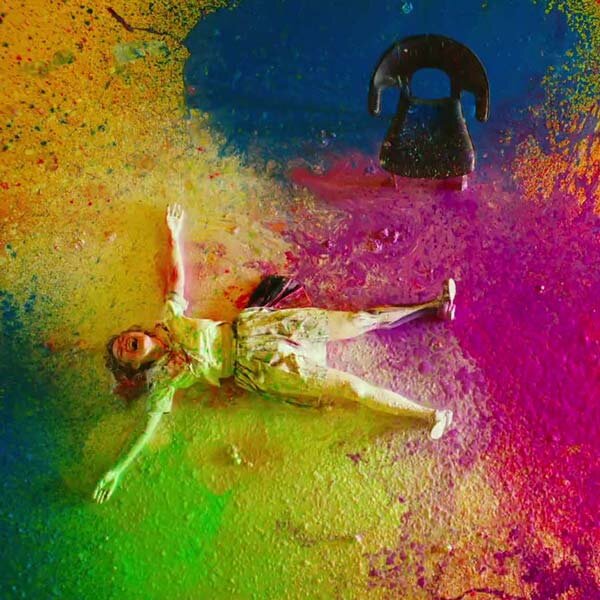

The three main categories of kabuki play are jidaimono (early historical and legendary stories), sewamono (contemporary tales post-1600) and shosagoto (dance dramas). In the video above you can see the dance performance by Nakamura Umemaru at the Portland Japanese Garden.

One of kabuki’s most central dramatic themes is the clash between morality and human emotions. Japanese moral ideals, both historically and today, rely heavily on the religious philosophies of Shinto, Buddhism, and Confucianism, which tend to emphasize qualities like devotion to one’s elders and community. However, emotions like revenge and love often get in the way of familial and other duties, creating the central conflict of most plays. These often end in tragedy.

Kabuki dramas sometimes include educational elements or attempt to provoke thought, but the main focus is on the cumulative sensory experience of witnessing the full visual spectacle come to life. Reality and consistency take a backseat to facets elaborate costumes and supernatural transformations.

© Natori Shunsen, 1951, Nakamura Utaemon VI playing Hanako in Musume Dojoji

Famous kabuki plays include:

Kanadahon Chushingura (Treasury of Loyal Retainers) - A jidaimono based on the famous tale of the 47 Ronin, a true story about a band of samurai who avenge their murdered master’s death before committing ritual suicide.

Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami (Sugawara and the Secrets of Calligraphy) - Based on the life of Heian era (794-1185) scholar Sugawara no Michizane. Exiled from Kyoto, a number of calamities befell his enemies upon his death, leading them to deify the scholar in order to appease his vengeful spirit.

Sonezaki Shinju (The Love Suicide at Sonezaki) - A sewamono about a forbidden love between an orphaned merchant named Tokubei and his lover Ohatsu, a courtesan. The pair commit suicide at a shrine dedicated to Sugawara no Michizane.

Bancho Sarayashiki (The Dish Mansion at Bancho) – A classic tale from the ghostly annals of Japanese folklore, where a retainer of the shogun falls in love with a servant maid in his family’s employ. When the maid, Okiku, refuses the lord’s solicitous advances, he throws her down a well – such was the nature of interclass courtship in feudal Japan – only to be haunted by Okiku’s ghost in return. Bancho Sarayashiki, and its now infamous well, served as direct inspiration for the 1991 novel Ringu (The Ring), subsequently developed into critically acclaimed horror films in Japanese and English.

Yotsuya Kaidan (The Ghost Story of Yotsuya) – Another work of ghostly fiction, Yotsuya Kaidan is a classic tale of revenge from beyond the grave told in five acts. The story has all the forbidden romance, conniving and betrayal of a Greek tragedy with some haunting and mental deterioration thrown in for good measure. Picture that being told through the sensual maelstrom of live kabuki.

4. Who Are the Most Famous Kabuki Actors and Playwrights?

In addition to Izumo no Okuni, the founding performer priestess, many key players shaped modern Japanese kabuki.

One of the most influential was Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725), a Japanese playwright so prolific he’s often compared to Shakespeare. He wrote The Love Suicide at Sonezaki as well as countless other scripts, many also about tragic suicides. Even though scripts aren’t considered as important as visual effects, Monzaemon is esteemed for perfecting and popularizing concepts kabuki is now known for.

Sakata Tojuro I (1647-1709) was an actor who collaborated with Chikamatsu Monzaemon. He became favored for his realistic and gentle acting style. Around the same time, Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660-1704) rose to prominence as a bombastic and ostentatious performer. Tojuro’s style was perfect for romantic stories; Danjuro’s for bloody tales of war and conflict. These styles became favored and are emulated to this day.

Both “Sakata Tojuro” and “Ichikawa Danjuro” have carried on as yago, stage names handed down to the actors who continue their methods. Other names taken from famous players have applied to several generations of performers, including Ichikawa Ebizo, Matsumoto Koshiro, and Nakamura Kanzaburo. Each new generation adds a number to the end of their name—contemporaries include Ichikawa Danjuro XII and Sakata Tojuro IV (whose lineage was broken for over 200 years before recently undergoing a revival).

Bando Tamasaburo V is possibly the most revered onnagata (female-character actor) still exceling at his craft. The 71-year-old, known for his feminine features and elegant gait, has been on the stage for over sixty years, following in the footsteps of his adopted father (Bando Tamasaburo IV). When asked by his friend and admirer, the author Alex Kerr, “Why did you want to become [a kabuki] actor?”, Tamasaburo V answered, “Because I longed for a world of beauty beyond my reach.” Perhaps this best contextualizes why, after all these years, young actors still yearn to join the archaic world of kabuki.

5. What are the Key Elements of a Kabuki Performance?

By now you know kabuki plays combine many cohesive elements, most notably song and dance. Here is a more detailed look at the major components of a kabuki play and how they work together.

Song

Music, created by both singers and instruments, helps set the narrative tone and pacing of a scene. Songs may be performed by one or many singers (utakata) at a time, and are usually accompanied by a shamisen, a type of Japanese lute. Other instruments can be used to create sound effects or act as cues for the actors. Depending on the performance, the musicians may be offstage entirely, positioned in the back or off to the side of the stage, or even directly incorporated into the action of the play.

Dance

Dance numbers are inserted into performances at almost any opportunity. However, kabuki acting is so stylized it’s indistinguishable from dance most of the time. Actors are trained to move and gesticulate using dance-like motions, meaning dance is an integral part of all kabuki plays. The movements differ based on the character: onnagata (female characters) flow daintily while doki (comedic characters) bounce jauntily. Many performances end with a lively dance finale (ogiri shosagoto) featuring the whole cast.

Performance Techniques

Actors employ many choreographed movements resembling dance, including:

Tachimawari: a stage combat technique. Choreographed fighting can be hand-to-hand or use swords.

Roppo: movement that simulates walking or running. Usually paired with upbeat drums.

Ningyoburi: the act of one actor controlling another’s movements, as if a puppeteer. This technique was inspired by bunraku, Japanese puppet theater.

Hikinuki: a specialized technique that involves changing one’s costume onstage, often perfectly timed with music.

© Peabody Essex Museum, Uchikake Kimono for Kabuki, 19th Century

Costumes

Since kabuki dramas tend to be set in the past, performers usually wear kimono, Japanese traditional clothing. Styles range from practical and subdued to cumbersome and extravagant. One of the most important skills of the actors is simply manipulating and moving in their heavy costumes; no easy feat. The costumes and accompanying wigs are made by hand by skilled artisans and are sometimes ornately woven with fine silver and gold threads.

Makeup

Known as kesho, kabuki makeup is based on a character’s traits. Actors’ faces are coated with oshiroi (white paint) to make them both more visible and dramatic. Then, colored lines are added to enhance their features as well as describe their character. Red represents qualities like passion and anger; blue symbolizes evil or sadness. The patterns differ depending on the character’s gender. Supernatural beings like ghosts and demons wear the most dramatic makeup. Actors apply their own makeup so they can better understand their character. Alternatively, sometimes decorated kabuki masks are used, though these are more common in noh theater.

Kabuki Mask

Set design and props

Stage decorations are lavish and typically include complex machinery. Moving lifts, traps, and curtains allow the performers and backgrounds to undergo astonishing transformations. For instance, an actor may suddenly disappear from the stage and reappear in the audience, or a background may revolve to simulate a ship moving across water. Apparitions and demonic characters are often suspended in midair with steel wires, a process called chunori. When actors themselves need to transform, a very useful player is the koken. Koken are stage assistants who help actors with costume changes and props. They often wear all black to maintain the illusion that the characters are transforming on their own.

Audience participation

During performances, it’s not unusual for audience members to shout and cheer for their favorite actor when he appears onstage or to applaud when something exciting occurs. Performers sometimes even address the spectators directly. It was only in later years that a stage separated the performers from the audience at all.

6. Kabuki in Popular Culture

As with many of Japan’s traditional art forms, kabuki has long since past its popular heyday. It still does a decent trade in the traditional centers of Tokyo and Kyoto, and holds enough historical allure to attract culture-hungry tourists. But where kabuki is perhaps most prevalent today, is in the influence it has had on other artistic mediums.

Anime is a prime example. When on roaring diatribes or eye-bulging monologues, anime characters tend to act in a distinct manner: they utilize hyper-stylized body movements and facial contortions to accompany the vocals. Moreover, anime often relies on visuals as much as story, exposition or character development. This is highly reflective of the characteristics which define kabuki. It’s not all that clear, however, whether these techniques of storytelling were deliberately appropriated from kabuki, or are merely hangovers of their cultural ancestry.

Kabuki is also thought to have influenced Western theater since it was introduced to colonial travelers in the late 1800s. Namely, it was the introduction of abstractionism in the West – in lieu of more realistic styles of storytelling – that had the artistic imprint of kabuki. Tennessee Williams’ later plays (which included In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel) drifted away from the trademark realistic dialogue on which he built his fame. He was derided by many Western critics at the time for doing so. Yet, some point to the influence of kabuki as the reason for this change in his oeuvre.

Beyond Williams, abstractionism became the leitmotif of many Western writers and filmmakers throughout the 20th century. Various kabuki plays have even been reimagined for the big screen, many of which have made it overseas (both in localized versions and in translation): The 47 Ronin, The Ring, The Ghost Story of Yotsuya, and Shin Heike Monogatari to name a few.

7. Where to See Kabuki In and Outside Japan?

Kabukiza Theater in Tokyo

Today, kabuki performances occur all over Japan and sometimes even tour overseas. A performance is typically divided into segments, one in the early afternoon and one in the early evening. Each segment is further divided into acts. Tickets are usually sold per segment, although in some cases they are also available per act. Tickets start at around ¥2000 ($18) for an act; depending on the seating; a full segment can cost up to ¥250,000 ($2,250)! Formal dress isn’t required to attend, but very casual or revealing clothing and shoes aren’t appropriate either.

Tokyo

Tokyo has three kabuki theaters, Kabukiza, Shinbashi Enbujo, and the National Theater. Kabukiza is the oldest; it originally opened in the early 1900s, but was recently renovated based on the original design. Kabukiza and the National Theater have English audio guides for rental, while Shinbashi Enbujo does not usually provide English guidance.

歌舞伎座 (Kabukiza)

Address: 4-12-15, Ginza, Chuo-ku, Tokyo (see map)

Website: kabuki-za.co.jp

Hours: See the schedule here.

新橋演舞場 (Shinbashi Enbujo)

Address: 6-18-2, Ginza, Chuo-ku, Tokyo (see map)

Website: shinbashi-enbujo.co.jp

Hours: See the schedule here.

国立劇場 (Kokuritsu Gekijo)

Address: 4-1, Hayabusa-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo (see map)

Website: ntj.jac.go.jp

Hours: See the schedule here.

Kyoto

© Michael Maggs / Creative Commons, Minamiza Theater in Kyoto

The birthplace of kabuki is home to the famous Minamiza Theater. It was founded in 1610, but the current building was constructed in 1929, across from the same river where the priestess Okuni performed. English audio guides are available.

南座 (Minamiza)

Address: 198 Nakanomachi, Shijodori Yamatooji Nishiiru, Higashiyama, Kyoto (see map)

Website: shochiku.co.jp/play/theater/minamiza

Hours: See the schedule here.

Osaka

Osaka’s kabuki theater is the Shochikuza Theater, first opened in 1923. It provides English pamphlets and audio guides.

大阪松竹座 (Osaka Shochikuza)

Address: 1-1-19, Dotonbori, Chuo-ku, Osaka (see map)

Website: shochiku.co.jp/play/theater/shochikuza

Hours: See the schedule here.

Fukuoka

The Hakataza Theater in Fukuoka, on Japan’s southern island of Kyushu, was constructed in 1996. English pamphlets are available for most productions.

博多座 (Hakataza)

Address: 2-1 Shimokawabatamachi, Hakata-ku, Fukuoka (see map)

Website: hakataza.co.jp

Hours: Front desk open daily from 10am-6pm. See the performance schedule here.

Abroad and Online

The Shochiku Theater is one of the most famous traveling kabuki troupes. Established in the 19th century, this lineage of actors has performed in various regions across Asia, Europe and North America since the 1920s. Information for overseas tours can be found on their website. Kabuki Web also provides information on performances abroad, although future international tours are currently up in the air in light of the ongoing pandemic.

The Portland Japanese Garden is one of the centers of Kabuki outside of Japan. In the video above you can see a mesmerizing dance performance by Nakamura Umemaru at this very location. Za Kabuki, an Australia National University theater group which strives for inclusivity by utilizing both male and female actors, are also ratcheting up interest in kabuki overseas. The troupe often performs at live events across Australia, and take private bookings.

In the post-pandemic era, there are a lot more options for watching kabuki online too. YouTube is a treasure trove of classic kabuki pieces and vignettes – all of which are available for free. You can watch Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees (featured above) and Kanadahon Chushingura (Treasury of Loyal Retainers) – the latter of which comes complete with English subtitles. And though it may make purists turn in their graves, a novelty kabuki-Star Wars collaboration is available on YouTube. Kabuki Web also has some great introductory videos to the craft.

8. Books to Learn More About Kabuki

Though we have covered all the basics of kabuki in this introductory primer, it has scarcely scratched the surface of this deep and complex world. If you want to learn more there are plenty of insightful books on the subject. Here are five recommendations:

Kabuki, A Mirror of Japan: Ten Plays That Offer a Glimpse Into Evolving Sensibilities by Kesako Matsui

Kesako Matsui’s Kabuki A Mirror of Japan is a great starting point for those new to the world of kabuki. Through the lens of ten individual plays in chronological order, Matsui looks at everything that shaped kabuki over the centuries, from how it evolved from its 17th-century pulp satire origins to how it was influenced by time and place. A must-have on the bookshelf of any kabuki enthusiast.

Kabuki, A Mirror of Japan, Available at Amazon

Edo Kabuki in Transition: From the Worlds of the Samurai to the Vengeful Female Ghost by Satoko Shimazaki

Another work that focuses on how kabuki has changed over time, Satoko Shimazaki’s Edo Kabuki in Transition is really about the golden years of the art form. Researched with scholarly levels of rigor, the book also looks at the reciprocal effect that kabuki had on society: how it gave people a sense of shared history and helped frame the nascent identity of Edo under Shogunal control. A great option for those who want more of a deep dive into kabuki culture.

Edo Kabuki in Transition, Available at Amazon

Kabuki: Five Classic Plays by James R. Brandon

There’s perhaps little point in digging into the world of kabuki without being able to understand the plays themselves. With James R. Brandon’s Kabuki: Five Classic Plays, you can read in English some of the best stories to take to the kabuki stage. The plays were translated from taped recordings of live performances and feature commentary and annotations helping bring them all vividly to life.

Five Classic Plays, Available at Amazon

Kabuki Plays on Stage: Brilliance and Bravado, 1697-1766 by James R. Brandon

The spiritual successor to Kabuki: Five Classic Plays, this follow-up work by James R. Brandon features 25 individual plays in translation split over two volumes. The first volume of Kabuki Plays on Stage: Brilliance and Bravado focuses on the early years of kabuki when the artform, still relatively new, was perhaps at its most chaotic and vibrant. Again, a great deep dive for diligent students of kabuki theater.

Kabuki Plays on Stage, Available at Amazon

The Kabuki Theater of Japan by A. C. Scott

The Kabuki Theater of Japan is the ultimate kabuki handbook. Over 300-plus pages, author A. C. Scott introduces readers to the world of kabuki, analyzes styles and acting techniques, covers everything from famous playwrights to set design, and looks at some of the most famous plays to grace the stage. An excellent book that bridges the gap between scholarly works on kabuki and the more casual overviews for the layperson.

JO SELECTS offers helpful suggestions, and genuine recommendations for high-quality, authentic Japanese art & design. We know how difficult it is to search for Japanese artists, artisans and designers on the vast internet, so we came up with this lifestyle guide to highlight the most inspiring Japanese artworks, designs and products for your everyday needs.

All product suggestions are independently selected and individually reviewed. We try our best to update information, but all prices and availability are subject to change. As an Amazon Associate, Japan Objects earns from qualifying purchases.

ART | October 6, 2023