What is Bunraku? How to Enjoy Japanese Puppet Theater

by David McElhinney & Brooke Larsen | ART

Puppet theater can be found in many cultures, but few have refined the art as perfectly as Japanese Bunraku.

Bunraku (文楽) is a classical form of Japanese puppet theater using rhythmic chanting, and traditional music. Luckily, you don’t need to understand Japanese to experience it; bunraku relies heavily on visuals and sounds to tell stories, so it can be enjoyed by speakers of any language. Let’s take a look at the history and elements of this form of puppet theater unique to Japan.

Bunraku is one of the the three most famous Japanese traditional theater styles. Explore our essential guides to find out about Kabuki and Noh Theater.

1. What is Bunraku?

Bunraku has captivated Japanese audiences for centuries. Also known as ningyo joruri (人形浄瑠璃), which translates to something like “puppet lyrical drama”, bunraku plays come together though the fusion of visuals and sounds.

The elaborately constructed wooden puppets are the striking visual elements which anchor the action of each performance. The puppeteers clothe themselves all in black, so while they’re visible to the audience (unlike in traditional western hand puppet theater), the viewer’s eye is drawn instead to the life-like dolls they control. Further demanding the viewer’s attention, each bunraku puppet is dressed in vibrant robes and has complex moving parts, enabling them to convey a wide array of emotions.

The sounds support the onstage narrative. Joruri is a mix of chanting, which is usually done by a single narrator, and the music of the shamisen, a Japanese string instrument similar to a lute. This music blends together to simulate the dialogue and mood of each scene.

Bunraku performances regale the audience with stories of heroism, tragic love, and the supernatural. These tales typically come directly from Japanese history and legends. Though the plays depict times and traditions long past, they often center on human emotions still relatable to present-day viewers.

Unlike puppet theater from other cultures which tends to cater to children, bunraku is considered a serious artform accessible to all ages.

Bunraku and its components have been named both a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage and an Important Intangible Cultural Property of Japan for its impact on the nation’s culture. Check out the UNESCO video above to see why live bunraku is akin to witnessing a piece of living history.

2. Where Does Bunraku Come From?

© Sekino Junichiro, Eizo and Matsu-o-maru - Bunraku, 1956

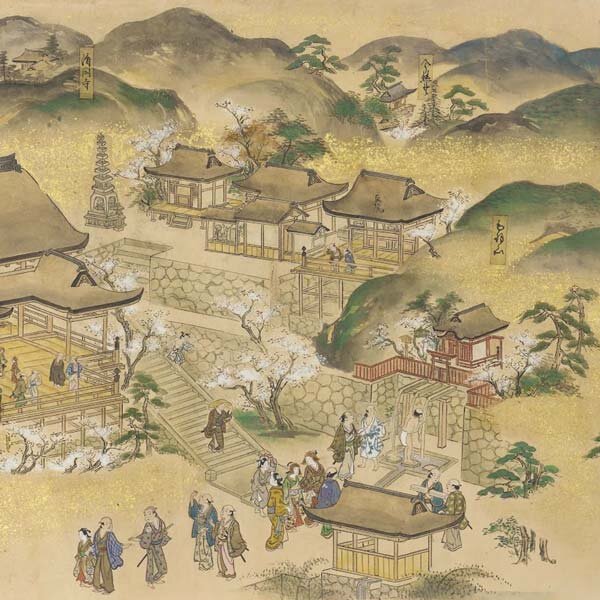

Bunraku theater first began in Osaka in the 17th century. Osaka in the 1600s was then much like it is today: a bustling merchant city revolving around trade from the major ports. To cater to the many travelers passing through, Osaka developed a vibrant entertainment center around its main central waterway, the Dotonbori canal. Many artforms blossomed in the Dotonbori district, including kabuki, but bunraku is one of the few actually created there.

Initially, bunraku was a form of pulp entertainment for commoners, but it evolved into a more artistic and refined practice over time. It rose to popularity when a playwright named Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724) began collaborating with the renowned chanter Takemoto Gidayu (1651-1714). Takemoto created a puppet theater in 1684 showing original plays that captivated the nation. Monzaemon wrote many of these, authoring so many successful scripts in his lifetime he is often referred to as the Shakespeare of Japan.

The term bunraku initially referred to a specific theater called the Bunrakuza, established in 1805 by Uemura Bunrakuken (1751-1810). Bunrakuken’s theater revived the artform, which had fallen into decline in Osaka and much of the Japanese mainland during the 18th century. Eventually, bunraku became the preferred term, although ningyo joruri is also used today.

3. What Do Bunraku Puppets Look Like?

Bunraku puppets are made of wood and are anywhere between one to four feet in height. The puppets don’t actually have full bodies; only the head, hands, legs, and feet are crafted. These are connected with string while the torso is simulated using a kimono. Male dolls have legs and feet, but the female dolls don’t because traditionally their clothing completely covered their bottom halves. Most of the body as well as the clothing are made by the puppeteers themselves.

Bunraku Puppet Head, 19th Century, the Met Museum

The heads and hands are generally carved by specialists, as these tend to be the most complex elements of each doll. Each facet of the head (kashira) is made to move, allowing the puppets to be expressive: the eyes blink, the mouth opens and closes, and the eyebrows move up and down.

Sometimes multiple heads are created for one character and these are switched out during the show to convey different emotions, or the aging process.

Bunraka Puppet, 20th Century, V&A Museum

Depending on the performance the head might even be made to transform entirely, morphing from the face of a human to one of a demon for example.

The size of the head varies depending on the character. Heroes and powerful beings have larger heads than common villagers and minor supporting characters.

4. How does it Work?

The three types of bunraku performers are the ningyotsukai (puppeteers), tayu (chanter), and the shamisen player. The puppeteers perform on the main stage (hombutai) while the tayu and musician sit on a partition off to the side (called a yuka).

It takes three puppeteers, usually hooded and clad in black as not to attract attention to themselves, to operate a single puppet. In lieu of strings, rods extend from the back side of the dolls. The main puppeteer is known as the omozukai. He or she uses their right hand to manipulate the right hand and face of the puppet. The left puppeteer, called the hidarizukai, controls the left hand of the puppet with his or her own dominant hand. A third puppeteer, the ashizukai, operates the entire lower half. Apprentices start as ashizukai and literally work their way up to omozukai. This training can take up to 30 years.

The tayu and shamisen musician work together to create the narration and emotion of the performance, respectively. Typically, a single chanter recites all the roles, though sometimes multiple narrators are used. Tayu are skilled in a variety of vocal ranges to convincingly portray a diverse cast of different ages, genders, and social classes. They read from a script written in traditional Japanese, so subtitles in modern Japanese are often incorporated so audiences can understand. The tayu sits next to the shamisen player, allowing them to harmonize are create the joruri. The joruri synchronizes perfectly with the puppets’ movements creating a truly impressive sight.

5. Who Are the Lost Puppeteers of Awaji?

Before Awaji island became an extension of the Japanese mainland via the Awaji Kaikyo Bridge – the world’s longest suspension bridge at almost 4km in length – it was a lone stretch of land in the Seto Inland Sea, shaped not unlike a giant T-bone steak. Though Awaji may not ring too many bells to foreign travelers, between the 17th and 20th centuries it was one of Japan’s true bunraku strongholds.

Historical documents show that as far back as 1741 there were 38 registered bunraku troupes in Awaji alone – an island less than 230 square-miles in size – many of whom toured the nation with their wooden performing companions. The Awaji puppeteers often performed in temporary outdoor fields, called nogake, such was the demand for live bunraku. They seemed to have made a particularly strong impression in Iyo Province – modern-day Ehime Prefecture, Shikoku – based on significant collections of masks they owned, depicting gods and animals, made by a famous Iyo-based mask craftsman, Menmitsu Yoshimitsu.

Throughout the entire Edo Period (1603 – 1868) the Awaji puppeteers enjoyed a prolonged purple patch of success – so much so they received sponsorship from a lordly benefactor in the form of the daimyo (feudal lord) of Tokushima. But the Meiji Restoration of 1868, coinciding with Japan’s rush to westernize, sounded the death knell for many puppet troupes and other practitioners of the traditional performing arts. In the subsequent 150-plus years, thanks to modernization and the destructive effects of World War II, bunraku has struggled to regain a following in Awaji approaching the glory days of old. Yet with the formation of the Awaji Puppet Theater in 1969, the tradition carved out a niche for survival.

© Awaji Puppet Theater

Awaji’s new ad hoc bunraku theater, built with a traditional bamboo interior in Fukura town in 2012, is home to a troupe of fewer than 20 performers, which until 2016 included master shamisen player Tsuruzawa Tomoji who died at the ripe old age of 103. The troupe has a repertoire of around 12 different stories, each around 45-minutes long and accompanied by English sheet translation for foreign guests. Plays are performed daily (bar Wednesdays) and are followed by meet-and-greets with the cast. The Awaji Puppet Theater also performs internationally in the US, Europe, Asia, and Oceania, and conducts a variety of educational programs closer to home, hoping to attract more future performers to the tradition.

6. Famous Bunraku Plays

Kanadehon Chushingura

Scene from Chushingura by Utagawa Kunitera

First staged in 1748 at Takemotoza theater in Osaka, Kanadehon Chushingura (roughly translated as Chushingura: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers) is one of the most enduring works of bunraku theater. The 11-act piece – initially written by the inimitable Chikamatsu Monzaemon shortly after the events on which it’s based and subsequently adapted by Takeda Izumo II a few decades later – is a thundering historical tale of loyalty and revenge, also receiving much acclaim as a kabuki performance, in the form of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and as a 1962 motion picture.

The story follows the famous 47 ronin and their crusade to avenge the death of their former master, En’ya Hangan. Following Hangan’s death at the hands of the Lord Morano’s treachery, the ronin embark on a bloodthirsty quest for the head of the feudal perpetrator. This leads to a climatic siege in the December snowfall at Morano’s mansion, and the ronin’s inevitable act of seppuku (ritualistic suicide). Kanadehon Chushingura is unique as one of the few pieces of bunraku to be introduced by a puppet narrator and as one of the first works of Japanese literature to receive English translation.

Love Suicides at Sonezaki

© Hiroshi Sugimoto / Courtesy of Odawara Art Foundation, Love Suicides at Sonezaki

Bunraku’s answer to Romeo and Juliet, the Chikamatsu Monzaemon classic Love Suicides at Sonezaki is a masterpiece of dramatic storytelling and love-struck tragedy. Written in 1703, the story was based on an actual love-suicide which took place only a month prior to Monzaemon’s recreation of the tale. Unlike Shakespeare’s famous romance, the twin protagonists come from the lower rungs of society: Ohatsu, the pleasure house courtesan, and Tokubei, a soy sauce merchant. The plot is simple: Deceived by a friend and branded a thief, Tokubei sees suicide alongside the willing Ohatsu as the only end to his tragic tale.

Love Suicides at Sonezaki became so influential that it simultaneously rescued the Takemotoza theater from the clutches of bankruptcy, inspired a raft of copycat suicide-romance literature, and (inadvertently) drove many love-stuck couples to re-enact the final scenes of the play with fatal consequences (subsequently causing the government to outlaw love-suicide plays).

The Battles of Coxinga

The Battles of Coxinga, by Utagawa Kunisada

Kokusen’ya Kassen (1715), better known as The Battles of Coxinga, is another enduring work from the deft quill of Chikamatsu Monzaemon. It was arguably his most popular play, going on a marathon 17-month run in Osaka following its first staging in November that year.

The narrative follows Sino-Japanese historical figure Coxinga and his quest to restore the Chinese Ming dynasty in favor of the Qing usurpers. The play was unusual in the fact it dealt with foreign subjects during the time of Japan’s 250-plus year isolation from the rest of the world – yet this, along with its historical accuracy, may go in some way to explaining the piece’s success.

7. Where to Watch Bunraku?

Bunraku underwent another hiatus during World War II, but performances resumed only a year after the conflict ended. By the end of the 20th century, the two main bunraku theaters of Japan had opened in Osaka and Tokyo, spearheading the revival that continues today.

Osaka

Bunraku continues to thrive in Osaka, the city where the craft was created. The National Bunraku Theater, which opened in 1984, is its headquarters. It’s located in the city’s Nipponbashi neighborhood, adjacent to downtown Dotonbori. English headsets are available for rental for most performances and English brochures are provided free of charge.

国立文楽劇場 (Kokuritsu Bunraku Gekijo)

Address: 1-12-10, Nipponbashi, Chuo-ku, Osaka (see map)

Website: ntj.jac.go.jp

Hours: Open during performances. See the schedule here.

Tokyo

The National Theater opened in the capital in 1966. Bunraku plays are performed on the theater’s small stage. Earphone guides and flyers in English are available for a fee.

国立劇場 (Kokuritsu Gekijo)

Address: 4-1, Hayabusa-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo (see map)

Website: ntj.jac.go.jp

Hours: Open during performances. See the schedule here.

Bunraku is one of the most important and unique facets of Japanese art. Seeing a performance is a valuable way to experience the country’s fascinating history, distinct character, and stunning visual and performance art all in one go. Make sure to check out a showing next time you’re in town!

Awaji

The venerable Awaji Puppet Theater runs performances almost daily, excluding Wednesdays and when the troupe is periodically performing elsewhere in Japan or abroad. The performance schedule is available on the website.

Address: Ko-1528-1 Fukura, Minamiawaji, Hyogo (see map)

Website: awajiningyoza.com

Hours: Open during performances. See the schedule here.

8. Where to Watch Bunraku Online?

During the pandemic, many of Japan’s traditional performing arts, already facing straining budgets and dwindling public interest, face existential threats. The government’s stay-at-home requests ensured live performances were suspended overnight, slashing many bunraku performers revenue streams instantaneously.

Several stories came to light as the bunraku tradition and its practitioners attempt to keep themselves in business: the Osaka-based bunraku master, Kanjuro Kiritake, who turned to making puppets for children; the resumption of puppet festivals across the country in 2021 after a Covid-19-enforced hiatus; or the imposition of strict guidelines for theater attendance (temperature checks, QR code tickets, masks) when they finally reopened.

Mirroring the rest of the art world in 2020, there was also a shift to online performances, including the National Bunraku Theater’s 35th-anniversary performance of Kanadehon Chushingura. Here’s how you can watch bunraku online today:

The National Theater Online, operated by the Japan Arts Council, features videos with snippets and scenes from some of Japan’s most famous bunraku plays.

The Bunraku Puppet Theater Facebook Page also publishes full-length performances, famous enacted scenes, and relevant news stories on a regular basis:

At the Mellow In Japan Youtube channel, you can also watch some great introductory videos to the bunraku tradition.

ART | October 6, 2023