Ikebana: All You Need to Know About Japanese Flower Art

by Shozo Sato | ART

© Shozo Sato, Sunamono Ikebana

Japanese flower arranging, or Ikebana, has come a long way from its humble roots as temple offerings centuries ago. Today it is a popular and innovative living art, unique to Japan, that is cherished by both experts and novices.

Ikebana master Shozo Sato’s first began his mission to explain Japanese Ikebana to Western audiences over 50 years ago. In his latest volume, Ikebana: The Art of Arranging Flowers, he reveals the groundbreaking advances of the last few decades.

In this article, Sato Sensei discusses the different styles of Ikebana, and includes some of the techniques and lessons that you will need to create your own floral art. Whether you’re new to Ikebana, or simply looking for inspiration, you will love this selection of incredible arrangements as well as the invaluable suggestions for creating your own.

When you’re ready to learn more, check out Ikebana in the The Art of Arranging Flowers, available on Amazon.

2. Where Does Ikebana Come From?

1. What is Ikebana?

© Shozo Sato, Freestyle Maple Ikebana

Ikebana (生花) means living flowers. The Japanese art of flower arranging has been described as being at once more subtle, more sensitive, and more sophisticated than the methods of arranging flowers usually employed in other cultures. This is so because Ikebana is an art in Japan in the same sense that painting and sculpture are arts elsewhere.

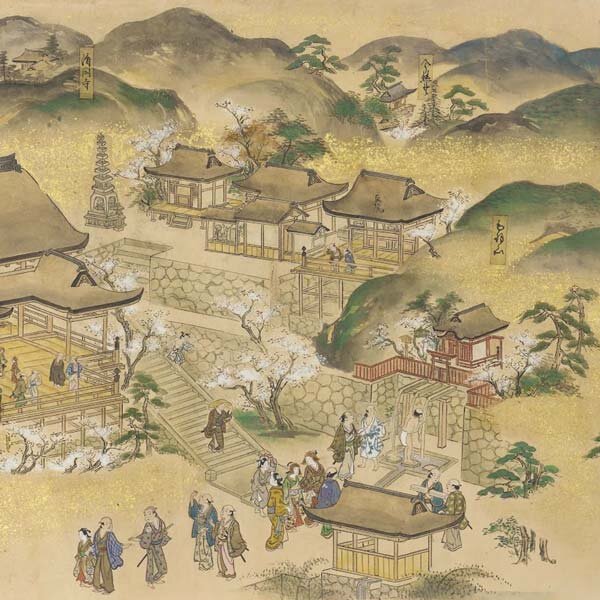

2. Where Does Ikebana Come From?

© Shozo Sato, Sunamono Rikka and Dozuka Rikka

Simple floral arrangements were made as early as the 7th century, when Buddhism was introduced to Japan from China. It was the custom to place flowers before images of the Buddha, and over the centuries these floral offerings acquired a fairly elaborate form.

During Heian times (8th to 12th centuries) it was a common custom to send poetry attached to a flowering branch as an expression of admiration and sentiment.

With the ascendency of the samurai class from the 14th century, feudal lords gained stature and supremacy, and they wished to display their wealth and power. The first tokonoma, or alcoves, were built in their homes and palaces no doubt to display suits of armor, but once the unification of the nation was established and peaceful times arrived, art objects, including flower arrangements, began to be displayed.

3. Ikebana Arrangements & Styles

I) Rikka

© Shozo Sato, Rikka Flower Arrangment

The early Buddhist floral decorations were intended to symbolize the idealized beauty of paradise, and as a result they were generally both ornate and sumptuous. The same attributes were preserved in Rikka – the first Ikebana style – which aimed not so much at revealing the beauty of flowers as at using flowers to embody an elevated concept of the cosmos.

Rikka’s structural rules – called positions – guide the basic composition of the style. The nine key positions were developed by the Buddhist monks, who incorporated Buddhist teachings into their flower arrangements.

Ikebana is a visual art that uses plant materials that come in a wide variety of forms. Depending on the materials, artistic judgment must be used to readjust the established forms. In the Rikka style, it is essential that the nine positions be honored; but doing so, with the understand that within this structure there is room for personal expression, is the secret to Rikka.

© Shozo Sato, Ikebana Positions

1. Shin: spiritual mountain

2. Uke: receiving

3. Hikae: waiting

4. Sho shin: waterfall

5. Soe: supporting branch

6. Nagashi: stream

7. Mikoshi: overlook

8. Do: body

9. Mae oki: front body

II) Seika

© Shozo Sato, Kenzan Seika

In contrast to the formality of Rikka’s strict Ikebana rules, other freer ways of arranging flowers were known as Nageire simply meaning thrown in. The distinctive feature of the Nageire arrangement was that the flowers were not made to stand erect by artificial means, but were allowed to rest in the vase naturally.

It is by no means accidental that the Rikka style is associated with the more traditional forms of Buddhism, while the Nageire style is associated with Zen, for Rikka arrangements grew from a philosophic attempt to conceive an organized universe, while Nageire arrangements represent an attempt to achieve immediate oneness with the universe.

By the end of the eighteenth century the interplay between Rikka and Nageire gave rise to a new type of flower arrangement called Seika, which literally means fresh-living flowers.

© Shozo Sato, Seika Flower Arrangement

In the Seika style, three of the original positions were retained: shin, soe, and uke (although now known as taisaki), creating an uneven triangle.

In a Seika arrangement, which is placed in the tokonoma alcove, the active empty space both within the arrangement and within the frame of the tokonoma are vitally important.

Historically, Seika arrangements were composed of one material – the exception being the more sumptuous arrangements created for the New Year’s celebrations. Today the rule has been relaxed, and arrangements made of one, two or three materials are common.

III) Moribana

© Shozo Sato, Freestyle Moribana

Until recent years, the tokonoma alcove, where Ikebana was traditionally displayed, was considered a sacred space, but it is no longer included in modern, Western-based Japanese architecture. Today’s open spaces require that Ikebana be viewed from all sides, from 360 degrees. This is totally different from the approach to Ikebana in the past. To be appreciated, Seika must be in a tokonoma and be viewed while sitting on the floor in front of the arrangement. The Moribana (piling up) category of Ikebana evolved as a way to create a more three-dimensional sculptural quality with the use of natural plants.

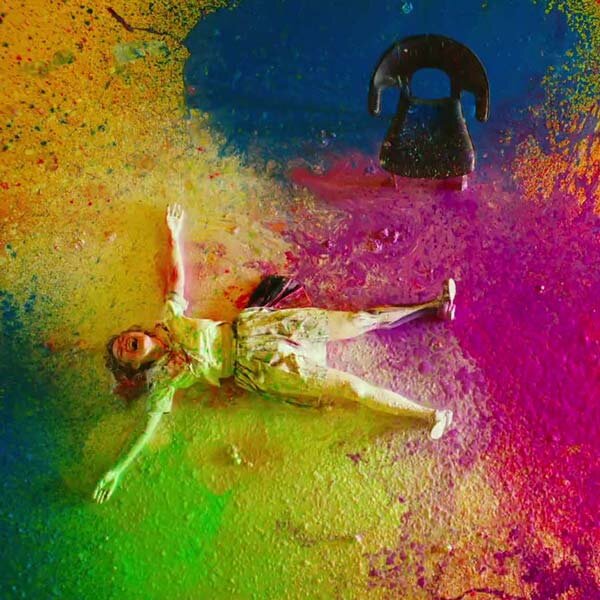

IV) Contemporary Ikebana

© Shozo Sato, Contemporary Ikebana

The concept and style of classic flower arrangements – such as Rikka and Seika – continue to be fundamental, but modern tastes have led to the use of a variety of materials not previously used in Ikebana. In this example, perhaps the unique flower vase with its three thin, painted lines inspired the artist to create this stunning arrangement. If plant materials were not used, this arrangement could be considered a contemporary sculpture.

4. Basic Ikebana Techniques

© Shozo Sato, Bamboo Arrangement

Ikebana can be translated as living flowers and, as with all living things, each type of plant has its own set of characteristics. The major characteristic that we concern ourselves with is whether a plant’s stem or branch is brittle or supple.

How to use heat to bend a branch

Many types of evergreen have heavy sap, which becomes soft when heated and hard again when cooled. Place the part of the branch you wish to bend over the candle flame, while gently bending it to the desired angle, then immediately plunge the heated section into cold water until completely cool. Always remember to hide burn marks from the viewer’s sight.

How to use scissors to create a sharply bent angle

Some branches such as maple or flowering plum cannot be sharply bent and will simply break in two. To make a sharp bend with these materials, use scissors to make a cut that is one-half the diameter of the branch, and gently open the break so that the upper bark overlaps. A series of these gentle bends will create the required angle.

How to use wire supports

Hollow-stemmed flowers can be easily straightened with thin wire, simply push the wire gently up from the bottom of the stem.

How to use kenzan

© Shozo Sato, Using Kenzan

The oasis that Western florists use is not recommended for Ikebana because the foam does not allow the angles of the plants to be readjusted. Most kenzan are cast with brass needles on a lead base, for weight. It is important to wash and rinse kenzan well after each use to keep them in good condition.

Cut the base of the flower stem at an angle, which makes it easier to insert and stabilize the branch.

For thicker branch stalks, cut a portion away to make the bottom of the branch thinner. Use both hands to push the branch forcibly onto the kenzan needles.

5. Lessons in Ikebana

© Shozo Sato, Nishu Ike

Become familiar with the individual components and their formations in lines. It is important to give the feeling of the energy of the plant growth, so toward the tip it becomes almost straight. An imaginary line from the tip of the shin to the very bottom should be perpendicular to the rim of the vase.

© Shozo Sato, Kakisubata Iris

Most plant leaves appear to be bilaterally symmetrical on either side of the main vein. Yet, upon close examination, often they are not all symmetrical. If this is the case, the wider side is called yang and the narrow side is called yin. Using this distinction, the wider side of the leaf must be toward the front of the arrangement, and the smaller side toward the back.

© Shozo Sato, Nageire Composition

For Nageire compositions, you won’t need to affix the dominant branch, instead, they sweep down at an angle 45 degrees from the tall vase, and leans 45 degrees forward. The size and weight of the floral materials will help determine the height and width of the vase to be used. To make the floral material stand in the desired position, some elementary principles of the dynamics of physics must be considered.

If you want to learn more about Ikebana, as well as enjoy many more peerless examples of the art, check out the Ikebana: The Art of Arranging Flowers, by Shozo Sato. Let us know what you think in the comments below.

About Tuttle Publishing: The leading publisher for books on the cultures, arts, cuisines, languages and literatures of Asia. Find out more at tuttlepublishing.com.

JO SELECTS offers helpful suggestions, and genuine recommendations for high-quality, authentic Japanese art & design. We know how difficult it is to search for Japanese artists, artisans and designers on the vast internet, so we came up with this lifestyle guide to highlight the most inspiring Japanese artworks, designs and products for your everyday needs.

All product suggestions are independently selected and individually reviewed. We try our best to update information, but all prices and availability are subject to change. As an Amazon Associate, Japan Objects earns from qualifying purchases.

ART | October 6, 2023