Nihonga: 12 Must-See Masterpieces of Japanese Painting

by Diccon Sandrey | ART

© Tetsu Katsuda, Evening, 1934, Adachi Museum of Art

Japanese painting covers a delightfully eclectic mixture of artistic styles, many of them quite familiar in the west: from zen art, through bold ukiyoe prints, even to the modern manga movie industry. Perhaps it’s a little ironic then that Nihonga, whose name literally means Japanese painting, should be among the least understood!

As you will see, there is no good reason why the Nihonga movement should continue to be overlooked, as Nihonga artists have produced some of the most compelling masterpieces of the last 150 years, such as the stunning bijinga (portraits of beautiful women), by Tetsu Katsuda.

Here we will take a look at some of the elements that make up the modern Japanese art style of Nihonga, which is as good a reason as any to enjoy these magnificent examples of Japanese art.

1. What is Nihonga?

© Shiho Sakakibara, White Heron, 1926, Adachi Museum of Art

Knowledge of foreign art was limited in Edo Japan, so when the country’s self-seclusion was broken open in 1853, Japanese artists were suddenly presented with an world of new ideas. Painting in the Western style, Yōga, became a source of fascination for art creators and consumers alike.

© Gyokudo Kawai, Spring Drizzle, 1942, Adachi Museum of Art

But as with most revolutions, the counter revolutionaries clamored to be heard too. The Nihonga movement was born of the desire felt by many to value those things that were distinct and beautiful about native Japanese art, whether that be natural themes like Sakakibara's White Heron, or homegrown landscapes like Kawai's Spring Drizzle.

2. Who created Nihonga?

© Kansetsu Hashimoto, Summer Evening, 1941, Adachi Museum of Art

Most histories of Nihonga will stress the role of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts opened by Okakura Tenshin and Ernest Fenollosa in 1889, and indeed the School was the first organization to formally separate Nihonga and Yoga, and to develop some principles for the former.

© Shiho Sakakibara, Japanese White-Eye and Plum Blossoms, 1939, Adachi Museum of Art

But of course no one person or institution created so inclusive an art movement as ‘Japanese painting’. Increasingly any painting created with traditional techniques and materials came to be seen as Nihonga. In fact, even in 1896, Tenshin himself said that “oil painting, if done by a Japanese, is Nihonga.”

Nihonga today covers a wide range of subjects and styles. Contrast the light-touch outline of Kansetsu Hashimoto's Summer Evening, with the intricate details of Shiho Sakakibara's Japanese White-Eye and Plum Blossoms

So how can we recognize a Nihonga painting?

3. Natural Colors

© Genso Okuda, Oirase Ravine (Autumn), 1983, Yamatane Museum of Art

Nihonga artists often make use of natural materials to make the required colors, including minerals such as azurite for blue and malachite for red. The finer the particles of this mineral pigments, the lighter the color. Various clays and chalk can be used for earth shades, while more vibrant red can be obtained from insects, such as the cochineal larvae or plants like sappanwood or garcinia trees.

Genso Okuda had access to the full complement of modern materials to create this breathtaking scene, neverthess, the colors he uses can be traced by to the very beginning of the Nihonga movement.

4. Gold and Silver

Kanzan Shimomura, The Beggar Monk, 1915

Japanese artisans had long achieved an unparalleled level of skill with gold and silver leaf, producing some of the thinnest examples in the world at only one 10,000th of a millimeter. Nihonga artists took full advantage of this such as in Kanzan Shimomura’s the Beggar Monk. The richness and brilliance of the gold covered background are used to contrast the viewers assumptions on the subjects’ life of blindess and poverty.

5. Silk and Paper

Taikan Yokoyama, Spring Dawn over the Holy Mountain of Chichibu, Silk, 1928

Where western artists usually favor canvas, proponents of nihonga argued for a return to the traditional materials of washi (literally ‘Japanese paper’) and silk. Both these materials absorb pigment in distinctive ways, and in doing so help to create the soft intermingling of color that is characteristic of Nihonga. You can find out more about washi paper in our Complete Guide to Washi Paper.

You can buy styles of washi paper today that were first popularized by the artists who used them, such as the Taikan style. For this painting however, Taikan Yokoyama uses a large screen of silk, which enables him to achieve the perfect misty atmosphere.

6. Space

© Shoen Uemura, Feathered Snow, 1944, Yamatane Museum of Art

One of the most distinctive characteristics of Japanese painting when contrasted with its European counterpart is the use of empty space. And of course, this distinction was carried into the twentieth century in the realm of nihonga art. In Shoen Uemura’s feathered snow, the great blankness of the paper successful conveys the sensation of inclement weather, where the horizon reduces to edge of your umbrella as you try to shelter from the cold.

7. Brush Strokes

Gaho Hashimoto, Moonlit Landscape, 1889

While yōga shies away from strong outlines, Nihonga does not have the same naturalistic intent. Art in the Japanese tradition is understood as a creative representation of reality, not an attempt to recreate the world on paper.

In Gaho Hashimoto’s moonlit valley, the rocks are clearly outlined, even through the mist. Nevertheless this vision is as real as any dream could be.

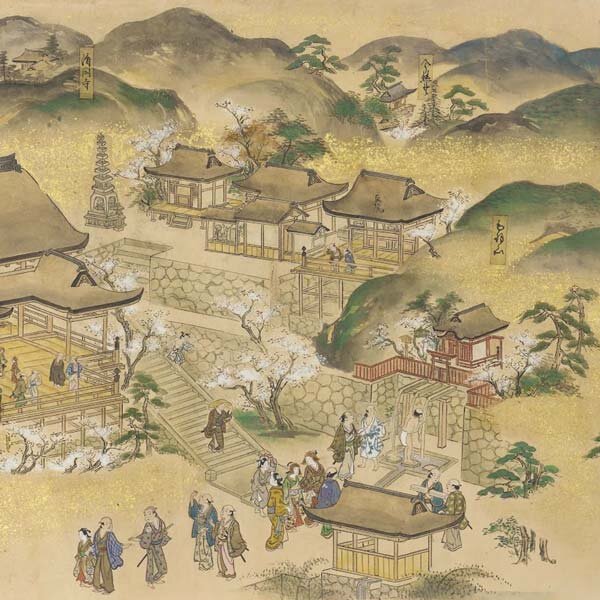

8. Traditional and National Themes

© Taikan Yokoyama, Mount Penglai, 1948, Adachi Museum of Art

At the birth of Nihonga in particular, the movement was a consciously nationalistic one. Schools and associations that taught and promoted the new Japanese art style would also encourage the inclusion of traditional Japanese themes, in particular religious iconography as in Taikan Yokoyama’s representation of Mount Penglai, a holy mountain in East Asian Buddhism.

© Atsushi Uemura, Sandpiper, 1994, Shohaku Museum of Arts

Of course, the variety of forms within Nihonga are innumerable, and just as Tenshin predicted, it has become difficult to draw a definitive line around just what exactly makes up this style of Japanese painting. The style and subject matter of Atsushi Uemura's Sandpiper seems quite far removed from his grandmother Shoen Uemura's renowned bijinga portraits. Yet, there is an indefinable presence that holds them together. Even within this brief overview, it is clear that Nihonga painting represents a form of beauty that makes us all richer for its presence.

Many of these incredible paintings can be viewed at the Adachi Museum of Art, Yamatane Musuem of Art, Shohaku Museum of Arts and the Sato Sakura Museum. Which of these Nihonga styles most speaks to you? Let us know in the comments below

LIFESTYLE | July 28, 2023