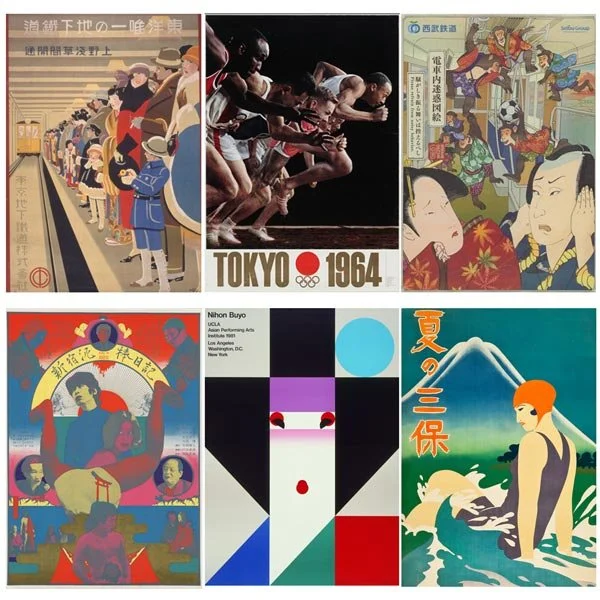

Katsushika Oi: The Hidden Hand of Hokusai’s Daughter

by Lucy Dayman | ART

Three Women Playing Musical Instruments, by Katsushika Oi, 1850

Katsushika Oi, is one of Japan’s most indirectly influential artists. Also known as the daughter of the much more famous Hokusai, the artist behind the Great Wave, Oi’s talents are evident from the few remaining works we still have of hers. Shrouded in mystery and with plenty of unanswered questions, let’s take a closer look at Oi, who some believe may be the real figure behind some of Hokusai’s most celebrated works (you can see some of these iconic prints when you visit Tokyo, take a look at our article Where to See Hokusai) !

Early days: The Hokusai Family

Although the artistic legacy of Hokusai is very well known, the lineage of his family is less well understood. It is widely assumed by historians that Hokusai’s daughter Katsushika Oi was born around 1800. Oi was born to Hokusai’s second wife, Koto, and had one brother and one sister, and one half brother and two half sisters from her father’s first marriage.

It’s said that Oi’s name - sometimes written as Oei, and also referred to as Eijo - was derived from おい, the Japanese equivalent of ‘hey you!’, which some historians report was what Hokusai called her, an embodiment of the playful nature of the pair. Julie Nelson Davis, associate professor of the history of art at the University of Pennsylvania, best described the relationship between the duo in a blog entry she penned for The British Museum which outlined the origin for Katsushika Oi’s name:

To call out ‘Oi’ in Japanese was then like it still is now, very informal and even rather impolite. When she replied with the lyric of a street-caller soliciting sales from passers-by, she must have been taking the mickey. Hokusai seems to have often called out ‘Oi, Oi’ when he wanted her. So Eijo used characters that replicated the sound of the word ‘Oi’ into an artistic name for herself…

This relationship would set the scene for the pair’s future. From early on, their dynamic was built on a foundation of playfulness, but also intimacy and mutual respect.

Katsushika Oi’s Paintings

Not a huge selection of Katsushika Oi’s paintings still exist, so it’s difficult to shape a comprehensive, visual, chronological outline of her career. However, the pieces we do have speak volumes, so let’s take a look at her career through such a lens.

Hua Tuo Operating on the Arm of Guan Yu, by Katsushika Oi, 1840s

Created sometime in the mid-1800s, this vivid piece, titled Hua Tuo Operating on the arm of Guan Yu is an excellent place to begin looking at Oi’s incredible talent. Incredibly detailed and very liberal with color, it sets a precedent of what to expect from many of Oi’s other efforts.

Display Room in Yoshiwara at Night, by Katsushika Oi, 1840s

Oi’s masterful use of color is best showcased in her piece Display room in Yoshiwara at Night, a depiction of Japan’s old brothel quarters. Building on the mystery that clouded the lives and careers of Japanese courtesans, Oi has painted these women in an artfully obscured fashion. The viewer sees enough to know who they are and their roles, but not much else.

Three Women Playing Musical Instruments, by Katsushika Oi, 1850

Three Women Playing Musical Instruments is another great example of Oi’s expert “paintings of beautiful women” as her father put it. Not one to be bound by artistic norms, Oi has presented one of the central figures of the composition with her back turned to the viewer, a very unusual artistic motif.

Cherry Blossoms at Night, by Katsushika Oi, 1850

This print, titled Cherry Blossoms at Night, is the embodiment of Oi’s career-long ability to take typical Japanese motifs and explore them in a different light. As with the geishas in Display Room, and the shamisen players in Three Women, Oi has taken something so commonly referenced in Japanese art - cherry blossoms - and hidden them in the shadows, making us question whether the power of this image lies in its physical manifestation, or rather the messages we assign to it.

Beauty Fulling Cloth in the Moonlight, by Katsushika Oi, 1850

This scroll, Beauty Fulling Cloth in the Moonlight, is an elegant piece of bijin-ga style painting (paintings of beautiful women). In a previous feature on some of Japan’s most important female artists, we commented on Oi’s “uncanny ability to utilize bold block coloring to capture the eye of the viewer” - here is an excellent example. By pooling all the imagery at the bottom of the canvass the shape and stylistic approach draw the viewer’s eye to the central hub of the action, however, by using darker shading at the top, the picture never feels unbalanced.

Print by Hokusai and Oi Katsushika

Although it’s said they worked on many projects together, this is one of the only confirmed collaborative prints by this father-daughter team in existence. A visual representation of the creative and familial harmony, Oi painted the floral outside, and Hokusai the middle.

Katsushika Oi’s Life and Career

Oi’s artistic career was - and will probably always be - overshadowed by her father’s legacy. From the outset it doesn’t seem like a situation Oi was actively avoiding, but rather something of a duty, this attitude is evident later on in her career when she went to work for her father and assist him in his old age.

Hokusai, however, would have been the first to admit that in many artistic pursuits his daughter’s work outshone his. In her blog piece, Davis quotes Hokusai as saying “when it comes to paintings of beautiful women, I can’t compete with her – she’s quite talented and expert in the technical aspects of painting.”

When she was younger, Katsushika Oi married fellow artist Minamisawa Tomei, but the pair didn’t have the most harmonious relationship, in large part arguably because Oi considered him to be a ‘comically’ mediocre artist. When they divorced, Oi moved back to live and paint with her father. The two were notoriously so focussed on their work, everything else fell to the wayside. It’s said they never cooked, or cleaned, once a house got too messy, they’d simply pack up and move somewhere else.

Davis also quotes the legendary ukiyo-e artist Keisai Eisen (1790–1848) who sang Oi’s praises, saying she “was “skilled at drawing, and following her father has become a professional artist while acquiring a reputation as a talented painter.”

When Hokusai reached his later stage of life, he developed palsy - it was during this time Oi worked closely alongside her father assisting him with an undisclosed number of his works. There are only around 10 images attributed to Oi specifically, but many assume that her hand played a much more active role in Hokusai’s life than she is credited for. Following her father’s passing Oi seemingly vanished from public view, adding an even deeper dimension to her legend.

Remind yourself of some of Hokusai’s most famous prints: Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.

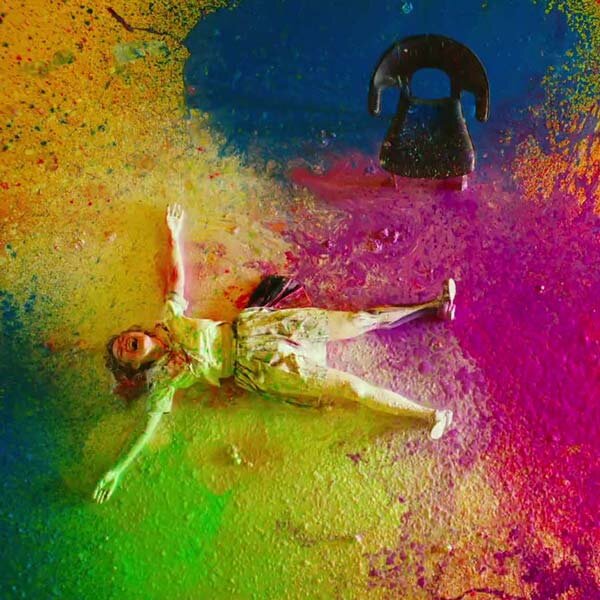

© NHK, Kurara: The Dazzling Life of Hokusai’s Daughter

As the years have gone on and historians have dug deeper into Oi’s legacy, they have uncovered some pretty fascinating biographical information. Japanese national braodcaster NHK produced a documentary on Katushika Oi titled Kurara: The Dazzling Life of Hokusai’s Daughter which detailed the artist’s importance in the Japanese art world.

Another great way to get a broader look at Oi’s life is by checking out the 2016 anime film ‘Miss Hokusai’ - a biographical journey through her early days up to her mysterious disappearance from view. It’s a contemporary-style look at one of Japanese art’s most intriguing figures. You can find out more and check out the trailer here.

If learning about Oi has got you interested in Japan’s artistic female legacy, be sure to check out our piece on some of history’s most important female painters.

Let us know what you think about Katsushika’s art, leave us a comment down below!

LIFESTYLE | July 28, 2023