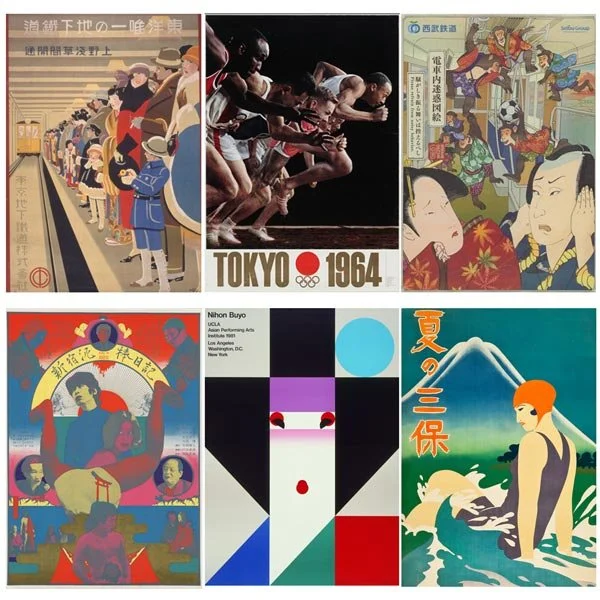

Kitagawa Utamaro: Discover Japanese Beauty Through his Masterpieces

by Diccon Sandrey | ART

Three Famous Beauties, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

Do you recognize Kitagawa Utamaro’s print The Three Beauties? If not the woodblock print itself, you have probably come across Japanese ukiyo-e of women drawn in a similar style: arrestingly elongated faces with straight delicate noses, and other features reduced to a mere suggestion. This has come to be the classical style in bijinga (美人画), or portraits of beautiful women.

But it wasn’t always this way! This vision of beauty was pioneered by the 18th century printmaker Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川 歌麿), whose work served as models for generations of woodblock artists.

We’re going to take a look at some of Utamaro’s most spectacular prints to see what an incredible and enduring contribution he made to Japanese art!

How did Utamaro’s Portraits Come To Be?

Detail of Courtesan Sitting on a Bench, Painting by Miyagawa Choshun, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The face of this courtesan is clearly not the same style at all.

Miyagawa Choshun was another highly influential figure in Japanese art who died in 1753, the same year that Utamaro was born.

Unlike later depictions, this the outline of her face is not painted in single line, but rather a pear-shaped curve that emphasizes her plump cheeks. Her nose is rounded, perhaps a little bulbous even.

Young Lovers and a Clock, Woodblock Print by Suzuki Harunobu

Moving forward half a century, take a look at the faces of these Young Lovers, and their curious voyeur, in this print by Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春信) from the late 1760s.

Their heads are drawn in a simple curve, much more oval in shape, but they retain a naturalistic proportion. Their features have become more pointed, but they are still approximately where you might expect them to be.

So how do Utamaro’s prints differ?

Utamaro’s Innovative Art

Woman with a Fan, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

Utamaro had been producing mainly book illustrations for much of his career until the 1790s when he began to focus on half-length bijinga prints. This format would have allowed him to explore his representations of the female face in great detail.

But where is the detail here?

The face of this Woman with Fan, has been supremely simple. The nose is almost a single line, the mouth a tiny butterfly of red. Instead, Utamaro draws attention the woman’s shape. Her head is stretched out of naturalistic proportions, and is now balanced upon a very narrow neck.

Beauty, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

Utamaro’s emphasis is made clear in this intimate portrait. The face in the mirror is boldly drawn, only the rouged lips confirm that it could not be man. But from the viewer’s perspective the erotically-charged bare shoulders and the slender nape of her neck reveal that this someone who Utamaro must have considered to be a considerable beauty.

Hairstyles in the Utamaro Prints

Hairdressing, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

The faces of Utamaro’s bijin may be simplified, but their hair has not escaped his attention!

The technique known as kewari enabled the individual strands of hair in Utamaro’s artwork to be carved into the woodblocks for printing, sometime as thin as a single millimeter. This imbues his prints with the sense of realism and warmth that is evident in this scene.

Wakatsuru, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

The loose strands protruding from this courtesan’s curls, and from the nape of her neck create an impression of unaffected beauty, even when absent-mindedly attending to other business.

Beauty, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

Such fine detail helps to add perspective beyond the two-dimensional facial features. The soft curl of this elaborate hairstyle is rendered transparent, which causes it to stand out of the image.

It wasn't just the hair itself that attracted Utamaro's eye for detail, but the range of exquisite implements that women used to support their elaborate hairstyles. In this print, kushi (comb), the glass or tortoiseshell comb is so finely made that you can see the subject's face quite clearly through it.

Men and Women in Utamaro’s Artwork

Samurai and Courtesan, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

It is obvious who is the samurai and who is the courtesan, but could you tell from their faces alone?

The answer is probably no. Judging from the shape, size, and features of the face, it is almost impossible to discern a difference between the men and women in Utamaro’s art.

Of course, there can be no confusion: their hair, costumes and poses are radically different, but there are more subtle indicators also. Utamaro tended to portray men with larger ears, and the courtesan’s delicate neck is not reflected in the samurai’s fuller throat.

Lovers in the Upstairs of a TeahouseWoman with a Fan, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

One of Utamaro’s most famous artworks ‘Lovers in the Upstairs of a Teahouse’ sidesteps this issue altogether, as neither person’s face is visible, giving full rein to the artist’s considerable talents in the portrayal of the other fine details of this captivating print.

True to form, Utamaro’s attention is mainly focused on the woman in the foreground. Her colorful clothes, naked nape and buttocks, and perfect hairstyle all combine to express his vision of the female form.

Heron Maiden, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

Kitagawa Utamaro’s prolific production of bijinga prints found fame within his lifetime, influencing the work of not only future ukiyo-e printmakers, but also painters across the globe, making him one of today’s most well-known, and expensive, Japanese woodblock artists!

What do you think of Utamaro’s work? Which one is your favorite print? Let us know in the comments below!

LIFESTYLE | July 28, 2023