The Tale of Genji in Japanese Art: 10 Must-See Masterpieces

by Will Heath | ART

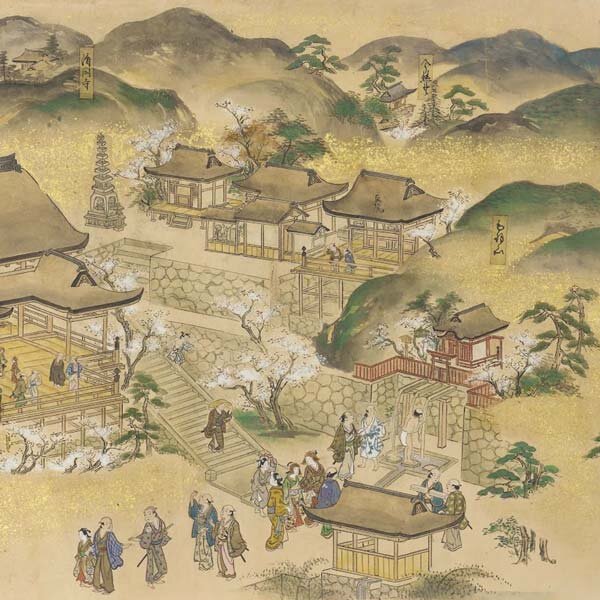

Fifty-Four Scenes from The Tale of Genji, late 17th Century, The Met Museum

Great art is often inspired by great literature, and with one of the world’s oldest literary traditions, it’s no surprise that artists in Japan have always found their muse in the country’s poetry and prose. One of the greatest and most impactful pieces of inspiration for so much of Japan’s artistry is a single story: The Tale of Genji. The story of this 11th century novel has been reimagined countless times in all forms of Japanese art, from painting and lacquerware, to ceramics and sculpture. Here are 10 masterpieces of Japanese art that help bring to life this classic tale.

What is The Tale of Genji?

© Maeda Masao, Fuji Ura-ba - The Tale of Genji, 1950s

The Tale of Genji is considered to be the world’s first novel. While storytelling and playwriting can be traced back for thousands of years, the novel as we know it today began in the early years of the 11th century – some time shortly before 1021 – with the Kyoto noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu. It is always worth taking a moment to consider how important it is for the world of literature that the first ever novel was written by a woman.

The novel itself follows the life and journey of an emperor’s son, Hikaru Genji, who has been removed by his father from the line of succession. Much of the novel is set both within and beyond the imperial walls of Kyoto, including the city’s surrounding mountains and villages. Most of the plot deals with Genji’s romantic relationships with various women, including his stepmother, and the tumultuous relationship he experiences with the one woman he is, in fact, married to. Inspired by the world in which Shikibu lived, the novel paints a vivid and colourful picture of imperial life during Japan’s Heian period.

© Maeda Masao, Early Bracken - The Tale of Genji, 1950s

The Tale of Genji’s author, Murasaki Shikibu, was a lady-in-waiting for Empress Shoshi. Empress Shōshi eagerly established herself a salon comprised of educated and refined ladies-in-waiting who were able to read and write – something almost unheard of at this time. Not only was Murasaki Shikibu one of these ladies-in-waiting, but Sei Shonagon, author of The Pillow Book – an equally famous and influential work of Japanese literature – was another. These ladies-in-waiting lived secluded and isolated lives within the imperial court, but they are nonetheless responsible for some of the greatest works of literature in all of Japanese history.

1. Dish in the Shape of a Princess

Fifty-Four Scenes from The Tale of Genji, late 17th Century, The Met Museum

In Saga prefecture is a town called Arita, famous for crafting Japan’s most refined porcelain during the Edo period. Much of Arita’s porcelain was crafted for foreign buyers, but this particular dish was commissioned by a local buyer and depicts a court lady of the Heian period. During the Edo period, the Heian period was heavily romanticised as a time of high art in Japan, where courtly ladies like The Tale of Genji author Murasaki Shikibu were writing literature and poetry. The woman depicted in this dish isn’t Shikibu herself, nor is she a woman specifically from The Tale of Genji. More vaguely, she captures the beauty, style, elegance, and fashion of women in Japanese courts during the regal Heian period.

Arita is worth a visit if you get the chance: it’s one of the 6 Best Japanese Ceramic Towns You Should Visit.

2. Tray with Scene from the Tale of Genji

Tray with Scene from the Tale of Genji, late 17th Century, The Met Museum

Shikki is a style of Japanese lacquerware that can be traced back thousands of years but saw something of a renaissance during the Edo period. Natural materials such as wood or leather would be coated in lacquer and decorated using various methods. The method here is known as maki-e: the use of gold inlay to depict the scene on the lacquer. This skikki tray was created during the early 17th century and depicts a specific scene from The Tale of Genji in which our protagonist passes by a former lover while riding in a cart and shares with her a sombre passing glance.

3. Incense Box (Kobako) with Scene from The Tale of Genji

Incense Box with Scene from The Tale of Genji, 19th Century, The Met Museum

This hand-crafted kobako incense box was carved during the Meiji period shortly before the turn of the 20th century and depicts a scene from Chapter 42 of The Tale of Genji. Kobako are popular collector’s items showcasing some of the most impressive Japanese lacquer work. Their purpose is to store the materials used in kodo – games and traditions surrounding the appreciation and comparing of incense. The scene from The Tale of Genji on this kobako is known as The Fragrant Prince, hence the connection between the story and incense. The prince, Kaoru, is Genji’s son, and at this moment is anxious and confused about the nature of his birth. The incense box even features a poem the prince writes which captures his anxiety and frustration.

Learn more about the tradition of Japanese incense in Choosing the Best Japanese Incense: 6 Things to Know.

4. Eight Views of The Tale of Genji in the Floating World

Woodblock Print from the series Eight Views of The Tale of Genji by Chobunsai Eishi, 1797, The Met Museum

In 11th Century China, drawings, paintings, and poems were created celebrating the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang (now Hunan Province). These depictions of natural scenery went on to inspired the Eight Views of Omi in Japan, which are now enormously famous ukiyo-e paintings by famed painter Hiroshige and various other painters of the Edo period. These paintings, in turn, provided the inspiration for the Eight Views of The Tale of Genji by Chobunsai Eishi. These pictures depict various scenes from the book, such as Chapter 41 Spirit Summoner and Chapter 19 A Thin Veil of Clouds, and all feature two beautiful women and landscape references to the Eight Views of Omi.

5. Imperial Carts (Gosho Guruma)

Imperial Carts, mid 17th Century, The Met Museum

Ruso Moyo (or the motif of absence) was a popular theme of 17th century Edo art when creating paintings for decoration, such as Japanese screens. This motif was used here in a depiction of imperial carts, which were used by Kyoto nobility during the Heian period. These carts in particular were inspired by a chapter in The Tale of Genji titled Leaves of Wild Ginger. In this chapter, attendants to Genji’s wife and former lover compete to plant their carts in the best place from which to view Kyoto’s Aoi Matsuri – a festival of the kamo shrines in northern Kyoto.

6. Noh Costume (Karaori) with Cypress Fans and Moonflower (Yugao) Blossoms

Noh Costume with Cypress Fans and Moonflower Blossoms, around 1800, The Met Museum

Much of Noh theatre – the oldest form of theatre still performed in Japan – is inspired by classic works of Japanese literature; The Tale of Genji being both the most obvious and most prominent. Actors in Noh theatre wear shozoku robes of various enchanting colours and patterns. This particular Edo period robe was made for a Noh performance inspired by Chapter 4 of The Tale of Genji. The robe is decorated by fans and moonflowers (known in Japanese as yugao – evening faces) which both feature in the chapter when Genji meets an enigmatic woman who has moonflowers growing on a vine outside her house, and who sprays Genji with moonflower petals from her fan.

Check out our Complete Guide to Noh Theater to find out more.

7. Fifty-Four Scenes from The Tale of Genji

Fifty-Four Scenes from The Tale of Genji, late 17th Century, The Met Museum

During the Edo period of Japan, the most famous and prominent school of painting was the Kano school, led by Kano Takanobu. During the time of his son, Kano Yasunobu (1613-1685), this screen depicting every single scene from The Tale of Genji was created. The novel is comprised of fifty-four chapters, and each one is captured here in two screens, hand-painted by a member of the Kano school and his assistant. In traditional Japanese style, still followed today, the screens read from top to bottom and left to right, and depict the entire story of The Tale of Genji in an almost comic book style that is faithful to the Kano school style of painting.

Find out more in Japanese Art: Everything You Might Not Know.

8. Noh Costume (Karaori) with Court Carriages, Cherry Blossoms, and Dandelions

Noh Costume with Court Carriages, Cherry Blossoms, and Dandelions, around 1900, The Met Museum

A Noh play from the Muromachi period of Japanese history is Lady Aoi (Aoi no Ue), attributed to the playwright Zeami Motokiyo (though he likely adapted it from an earlier script) and inspired by the character of the same name from The Tale of Genji. The play references an iconic scene from Chapter 9 of The Tale of Genji known as Battle of the Carriages. This explains the detail and decoration on this Noh costume, created for a performer of Lady Aoi to wear. It is decorated with ox carriages, dandelions, and sakura, reflecting the motifs of the chapter.

You can find out more about kimono motifs in Kimono Designs: 9 Must-See Japanese Masterpieces.

9. Handscrolls

Handscroll, mid 17th Century, The Met Museum

Kaiho Yusetsu, son of master ink painter Kaiho Yusho, was an Edo period painter descended from a samurai lineage. Though he initially had little luck as a commercial painter in his early days, connections to artists of the revered Kano school provided his work a renaissance; and this series of handscrolls, which depict every single chapter of The Tale of Genji, are a telling example of that. Not every painting on these handscrolls was completed by Yusetsu, however – some were evidently painted by an apprentice. But the detailed landscapes and the addition of calligraphy, which has been attributed to twenty-seven different calligraphers, is truly remarkable.

10. Writing Box with Warbler in Plum Tree

Writing Box with Warbler in Plum Tree, 18th Century, The Met Museum

One of the most famous traditional motifs of spring in Japan is the first song of the warbler. When it is heard, spring has officially begun. This motif is used in Chapter 23 of The Tale of Genji, and also captured here in captivating detail on this writing box. The lid of the box is decorated with a plum tree – flowering in the springtime – and a singing warbler in its branches. Reinforcing this is a depiction of a frog sitting amongst fallen plum blossoms – another motif of springtime. This particular writing box (suzuri-bako in Japanese) was created during the 18th century in the Edo period, but the production of lacquered writing boxes can be traced back to the 9th century. This writing box is an example of the common Edo practice of adding inlays of silver and gold to a lacquered wooden box.

ART | October 6, 2023