Japanese Embroidery: 9 Things You Should Know

by Sydney Seekford | CRAFT

Utamaro Embroidered Clutch, available at Japan Objects Store

Take stroll through any one of Japan’s historical craft markets, and you’re very likely to come across shishu – embroidery. While its use has changed over the centuries, the essence of Japan’s craftsmanship is woven into every piece of Japanese embroidery work.

The term shishuu encompasses all of Japan’s traditional embroidery craft, including the refined designs on kimono and the rustic, utilitarian applications of sashiko. Its use ranges from petite accents to entire paintings, holy tapestries in temples to eye-catching designs in modern fashion.

1. A Brief History of Japanese Embroidery

Shishu (刺繍) was introduced to Japan by Chinese sailors during the Asuka period (538–710 CE). This period marked the beginning of Japanese culture as we know it today.

The first Japanese embroideries were religious tapestries depicting images of Buddha in golden and silk threads. Early Buddhists used these images in prayer and decorated temples or sacred spaces with the imagery. The oldest surviving example of shishu is Tenjukoku Mandara Shusho, a Buddhist tapestry in Nara, commissioned in memory of Prince Shotoku by his wife.

As shishu techniques were refined and adapted, embroidery enjoyed a wider audience. Shubutsu (embroidered images of the buddha) expanded from official temple use to homes as the end of Buddhist law drew near.

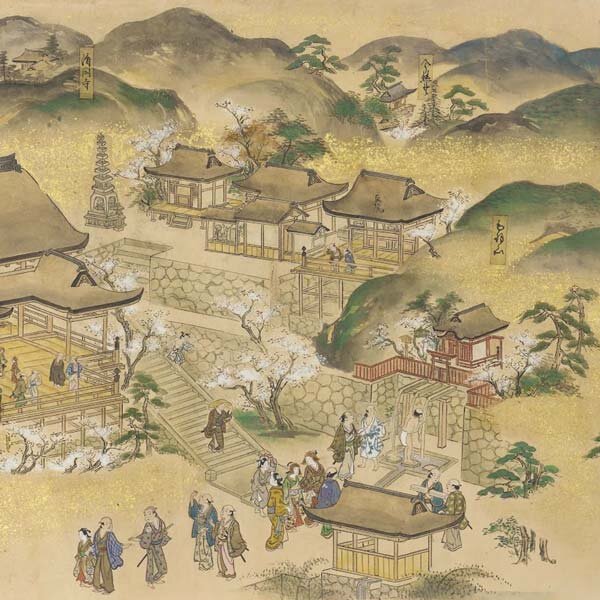

When the capital relocated from Nara to Kyoto, so did the art of Japanese embroidery. In the Heian period (794–1185 CE), shishu was used increasingly by the ruling classes, who applied it to decorate florid kimonos. Kabuki and Noh actors also began to wear brilliant costumes decorated with embroidery.

During the Muromachi period(1336 - 1573 CE), missionaries from Kyoto introduced shishu to the district of Kaga. The gold-wealthy area benefited greatly from the introduction of Japanese embroidery. The introduction of embroidery on the vestments of priests expanded the craft into its own form, now called Kaganui.

In the Edo period (1603 - 1868 CE), shishu techniques reached maturity. Japanese embroidery could be found on the uniforms of samurai and covering kosode kimonos from top to bottom. Edo (Tokyo) artisans adapted embroidery to create paintings in full detail with hundreds of colored threads. The designs grew gradually more luxurious until the Meiji government crackdown discouraged the merchant class’ frivolous lifestyle.

After the reformation, domestic Japanese embroidery activities slowed, forcing artisans to seek outside patrons and expanding the market for shishu abroad, where it capitalized on the European craze for japonisme. Today, Japanese embroidery is still alive and well, adored throughout the world and used in more places than ever before.

2. What is Special About Japanese Embroidery?

Like many of Japan’s traditional artisan crafts, shishu embroidery involves the specialized skills of several individuals to create one piece. The tight-knit industry can suffer from a single workshop lagging behind or an artisan experiencing illness. Depending on the style, different artisans may be in charge of dyeing and preparing the silk, hand-crafting needles, and designing the embroidery patterns before the design is ever actually stitched into being.

3. What Tools and Materials does Japanese Embroidery Use?

Vintage Silk Tancho Kimono, available at Japan Objects Store

Silk: Traditionally, silk was the material of choice for both base fabric and shishu threads. Its luster creates a unique appearance when used in three-dimensional designs. Silk is a strong, natural material.

Handmade Needles: A major producer in Hiroshima still provides most of the needles used for Kyonui embroidery. However, Kaganui uses its own form, and some artisans from all styles still choose to use cost-effective factory-made models in modern times.

Frames: The shishu frame is designed to support two-handed embroidery, unlike western embroidery frames. This allows artisans to work from above and below the piece.

Threads: Shishuu thread is dyed and twisted by embroiderers. Different schools use different dyeing techniques, producing thousands of colors. In the past, silk and gold threads were iconic to Japanese embroidery, but contemporary work also uses synthetic thread.

4. How is Japanese Embroidery Made?

Designs are drawn onto paper using traditional methods before being transferred using a glass or lightbox. In Kyonui, sometimes the design is dyed directly into the fabric. Designs for kimono often use as many as 30 colors of thread, while painterly designs can be much more elaborate.

Before stitching, the fabric is stretched over a specialized embroidery frame. Artisans have to account for shrinkage in the designs when the fabric relaxes. Hand-dyed threads are twisted to the desired length either by hand or using a tool. In Kaganui, threads are dyed for each piece, while other schools may choose from a set number of up to 2000 pre-dyed threads.

Kuniyoshi Embroidered Clutch, available at Japan Objects Store

The embroidery is performed by hand with special needles and then coated with an adhesive to set the design. Using over 100 different stitching techniques, artisans create a compelling but hardy design on the chosen fabric which will last for years.

5. What are the Techniques of Japanese Embroidery?

Vintage Silk Kimono, available at Japan Objects Store

Komanui (binding unthreadable patterns): Three-dimensional effects can be achieved with metallic or lacquered threads by binding them to the fabric with simpler threads. The term koma is applied to many techniques in shishu where tools help artisans achieve complex stitching.

Sashinui (sssential stitching): The most essential form of stitching used for designs and complimentary to the painting-esque techniques of Edonui. Short and long stitches alternate to create a clear, flat surface.

Vintage Silk Kimono, available at Japan Objects Store

Sagaranui (knotted stitching): Named for resembling mustard seeds, these create small, raised knots in the fabric for textural variety. It is one of the most characteristic traits of Japanese embroidery and is uncommon overseas.

Suganui (parallel stitching): Stitches applied parallel to the weft of the fabric create impressive design foundations while reinforcing the piece.

6. Regional Styles of Japanese Embroidery

Vintage Silk Kimono, available at Japan Objects Store

Kyonui: Kyonui is the oldest and most representative form of shishu. Kyonui is most often applied to Kimono and theater costumes traditionally, but most of the shishu available today is done in a Kyonui style.

Kaganui: Kaganui was carried to Kanazawa along with Buddhist teachings, Kaganui is used with Kagayuzen dyeing and features a slightly different technique. Pieces are less standardized and reflect the unique artistic sense of the region.

Vintage Silk Kimono, available at Japan Objects Store

Edonui: The most modern form of Japanese embroidery, Edonui innovates within Kyonui style to create painterly effects. Edonui is used for elaborate paintings made from thread. Lifelike images are created through relief stitching and extreme attention to detail.

Nagasaki: Nagasaki is close to China, so it enjoys a long influence from Chinese Buddhist embroidery. Nagasaki’s patterns incorporate unique maritime themes that faithfully reproduce images of buddhist treasures and sea creatures.

7. How to Enjoy Japanese Embroidery

Camellia Shibori Cotton Scarf, available at Japan Objects Store

Shishu is best appreciated through its many applications and unique imagery. Although it began as a part of Buddhist teachings, the art of Japanese embroidery finds a place in the world of Japanese women’s empowerment, modern faith, and even fine art.

8. Embroidery in Japan Today

Utamaro Embroidered Clutch, available at Japan Objects Store

After becoming an important part of society in the 600s, the stitch-by-stitch art of Japanese embroidery was practiced as a form of Buddhist meditation, like copying sutras. Creating shishu required virtues of perseverance and focus. Its beautiful results and moral value allowed the craft to expand into the world of Japanese women’s arts and education.

Female embroiderers found work in ancient Japan by stitching beautiful pieces for wealthy courtesans. The art form can still be enjoyed as a symbol of early female empowerment. Even the oldest remaining example has links to the role of women in Japanese society.

Golden Fuji Mini Coin Purse, available at Japan Objects Store

Embroidery expanded into the fine arts with its detailed recreation of historical paintings and scenes from life and nature. Powerful imagery has always featured prominently in shishuu embroideries. Gold is an essential feature of Japanese embroidery and has featured in its creation from its very first use as a religious ornament.

9. How to Buy and Display Japanese Embroidery?

Kimono have always been iconic canvases for Japanese embroidery, particularly in Kyoto and Kaga. While embroidered omamori charms can be purchased at shrines and promise good luck, children’s kimono traditionally lack the pockets and folds to keep them.

At its height, shishu craft was applied to the backs of children’s kimono as semamori, an embroidered talisman to keep evil from sneaking up behind kids. In contemporary fashion, sukajan jackets feature elaborate, painterly embroidery on the back of letterman-style or leather jackets.

Sukajan jackets are popular Japanese souvenirs. They were originally used to show off the wearer’s club and intimidate enemies from rival groups, but now sukajan can go for hundreds of dollars and feature characters from pop culture as well as traditional scenes of Japan.

Camellia Shibori Cotton Scarf, available at Japan Objects Store

Not all embroidery is obvious, of course, and traditional Japanese crafts are just as popular for their subtle beauty as their bold designs. Sometimes shishu is applied only as a finishing touch, an extra element of a comprehensive design, as with this traditionally woven scarf.

Kaganui used to be difficult to acquire, but the recent opening of a bullet train stop at Kaga Onsen brings Japanese visitors to the heart of this traditional form of Japanese embroidery. Paired with expertly dyed Kaga Yuzen products, stunning threads of Kanazawa gold and Noto lacquer take on an even more beautiful appearance.

Fine artwork made from shishu adorns folding doors and silk screens. Even decorative arts receive the influence of Japan’s unique traditional craft. Thanks to the popularity of shishuu born from Japan’s trade with the West, Japanese embroidery can now be enjoyed and purchased throughout the globe, through travels, and online.

ART | October 6, 2023