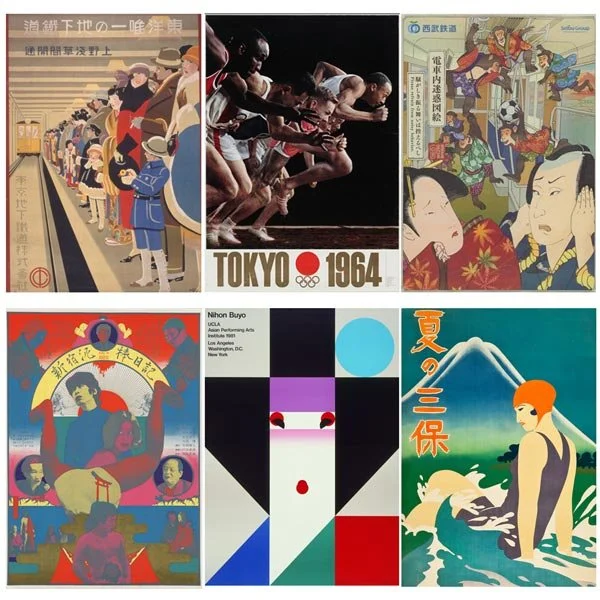

Why Utagawa Kuniyoshi was the Most Thrilling Ukiyo-e Master

by Cezary Jan Strusiewicz | ART

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The ukiyo-e movement, which bloomed in Japan between the 17th and 19th century, was one of the first times in Japanese history when art broke the bonds of social class and became something that appealed to the lowborn rather than just the aristocracy. Well, the rich lowborn, at least. For all the talk of ukiyo-e’s mass appeal, its woodblock prints and paintings were still products meant to be bought and sold, which is why they tended to focus on things Japan’s city-dwelling 1% enjoyed: travel, beautiful prostitutes, and kabuki actors, the 19th century Japanese equivalent of movie stars.

Ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798 – 1861), on the other hand, went beyond and below that, producing art that truly defined class by occasionally daring to appeal to the lowest common denominator. Like so:

Oiwake: Oiwa and Takuetsu, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

In the print Oiwake: Oiwa and Takuetsu, we see a balding ghost squeezing blood out of a clump of hair. The story behind this scene is that of the ronin Tamiya Iemon who disfigures his wife Oiwa’s face with poisoned facial cream. After Oiwa accidentally kills herself in a frenzied panic, she comes back as a ghost (or yokai), clutching the hair she lost due to the poison while her murderous husband screams in fright.

Popular Prints

The Ghost of Asakura Togo, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

It’s not really something that the aristocracy would want to display in their residences, but it was exactly the thing that appealed to everyday Japanese urbanites looking for some excitement in their lives. It’s also what popularized other woodblock prints by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, like Asakura Togo Borei (The Ghost of Asakura Togo) featuring a phantom of a wrongly executed man with brightly-colored blood on his neck, or the image of a bloodied, crucified corpse in The Ghost of Kozakura Togo.

If this is all too many bloodied corpses for you, try an artist with a more soothing sense of beauty:

Utagawa Kuniyoshi Samurai as Inglourious Heroes

Keyamura Rokusuke, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

In many ways, Utagawa Kuniyoshi was something like the 19th century Quentin Tarantino, especially with his focus on blood and gore, his subversion of established good taste in his chosen medium, and his ability to elevate them all to an art form. A big part of that was Utagawa’s use of bright, vibrant colors.

Takiguchi Watanabe, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Tarantino’s style can be best described as aggressive, dynamic, and very in your face. That’s also how Utagawa approached his work. He always tried to make his paintings and woodblock prints more vibrant, more violent, and more animated than his competitors because he knew that’s what the common man off the streets craved the most. And depictions of monsters and ghosts allowed him to do all that within one painting or print, which possibly laid down the foundation for a whole new Japanese art genre.

Another genre that may have the power to shock is shunga or erotic prints. But these were not actually considered as shocking as you might imagine. Find out more here:

Utagawa-esque Horror

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Most Japanese works of art depicting the supernatural were influenced by Heian-period depictions of Hell, which tended to be static and toned-down color wise. Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s artwork subverted all that, showing his audiences animated, colorful scenes of heroes slaying killer reptiles and giant monsters tearing down house walls etc. It’s no wonder then that some scholars consider Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s colorful monster/animal prints to be the precursor of modern day manga.

Tell us about your favorite Japanese monster prints in the comments below!

LIFESTYLE | July 28, 2023