Japanese Art: Everything You Might Not Know

by Japan Objects | ART

Mount Fuji by Yokoyama Taikan, 1940

Japanese art is one of the world’s greatest treasures, but it is also surprisingly hard to find up-to-date information on the internet.

This ultimate guide will introduce the most inspiring aspects of Japanese art: from the oldest surviving silkscreen painting, through magnificent 18th century woodblock prints, to Japan’s most famous modern artist Yayoi Kusama.

Art is created by people. That's why, in telling these stories, we pay close attention to their social and political implications. Through these 10 newly updated chapters you will learn, for instance, why nature has always been central to the Japanese way of life, and how the Edo era produced some of the most exquisite paintings of beautiful women.

The Japanese contemporary art scene is buzzing with innovation and creativity. We are pleased to share with you some of the most ingenious contemporary artists, craftswomen and men, who are often not as well-known internationally as they should be.

Let’s dive right in!

1. The Origins of Japanese Art

2. Zen & The Tea Ceremony

3. The Art of the Samurai

4. Edo Beauty in Ukiyo-e Prints

5. Traditional Japanese Architecture

6. The Rise of Japanese Ceramics

7. Japanese Art: The Splendor of Meiji

8. Modern Japanese Architecture

9. The Japanese Art of Craftsmanship

10. The Future of Japanese Contemporary Art

1. The Origins of Japanese Art

Great Wave off Kanagawa, Woodblock Print by Katsushika Hokusai

The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is undoubtedly one of the most famous Japanese artworks. It is no coincidence that this much-loved woodblock print has as its theme the formidable power of nature, and that it contains the majestic Mount Fuji.

© Taikan Yokoyama, Mount Penglai, 1948, Adachi Museum of Art

Nature, and specifically mountains, have been a favorite subject of Japanese art since its earliest days. Before Buddhism was introduced from China in the 6th century, the religion known today as Shinto was the exclusive faith of the Japanese people. At its core, Shinto is the reverence for the kami, or deities, who are believed to reside in natural features, such as trees, rivers, rocks, and mountains. To learn more about the Shinto religion, check out What are Shinto Shrines!

In Japan, therefore, nature is not a secular subject. An image of a natural scene is not just a landscape, but rather a portrait of the sacred world, and the kami who live within it. The centrality of nature throughout Japanese art history endures today, see for example these 5 Authentic Japanese Garden Designs.

This veneration for the natural world would take on many layers of new meaning with the introduction of Chinese styles of art – along with many other aspects of Chinese culture – throughout much of the first millennium.

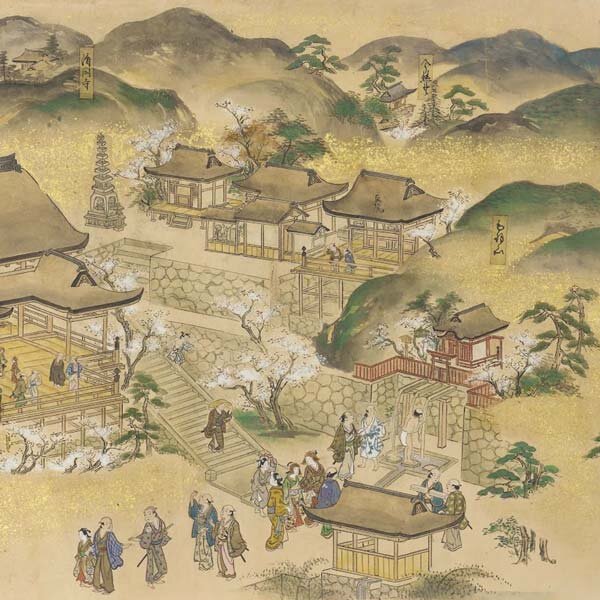

Senzui Byobu, Landscape Screen, 12th century, Kyoto National Museum

This meticulous Heian-era (794-1185) painting is the oldest surviving Japanese silk screen, an art form itself developed from Chinese predecessors (and enduring until today, see here for the Artistic Features of the Japanese House). The style is recognizably Chinese, but the landscape itself is Japanese. After all the artist would probably never have been to China himself.

Painting of a Cypress by Kano Eitoku, 16th Century, Tokyo National Museum

The creation of an independent Japanese art style, known as yamato-e (literally Japanese pictures), began in this way: the gradual replacement of Chinese natural motifs with more common homegrown varieties. Japanese long-tail birds were often substituted for the ubiquitous Chinese phoenix, for example, while local trees and flowers took the place of unfamiliar foreign species. One animal that is often seen in Japanese art is the kitsune, or fox. Here are some other Things You Should Know about the Inari Fox in Japanese Folklore! Themes of Japanese literature and mythology began to predominate. Classic stories such as the Tale of Genji can be seen throughout Japanese art, as you can appreciate in these 10 Must See Masterpieces.

As direct links with China dissipated during the Heian period, yamato-e became an increasingly deliberate statement of the supremacy of Japanese art and culture. Zen, another Chinese import, was developing into a rigorous philosophical system, which began to make its mark on all forms of traditional Japanese art. To learn more, see What is Zen Art? An Introduction in 10 Japanese Masterpieces.

View of Ama no Hashidate, Ink Painting by Sesshu Toyo, 1501, Kyoto National Museum

Zen monks took particularly to ink painting, sumi-e, reflecting the simplicity and importance of empty space central to both art and religion. One of the greatest masters of the form, Sesshu Toyo (1420-1506), demonstrates the innovation of Japanese ink painting in View of Ama no Hashidate, by painting a bird’s eye view of Japan’s spectacular coastal landscape. Sumi-e continues to be one of Japanese most popular artforms. You can give it a go yourself with our How-to Guide to Japanese Ink Painting.

Suruga Street, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Hiroshige

Perhaps nothing is as spectacular as the great Mount Fuji however. The perfect conical shape of the slumbering volcano, and the very real threat of its deadly fury, combine in an awe-inspiring entity that has been worshipped, and painted for centuries. You can see some examples over at Views of Mount Fuji: Woodblock Prints Demystified.

2. Zen & The Tea Ceremony

© Honolulu Museum of Art, Tea Ceremony Utensils

The evolution of the tea ceremony had a profound influence on the history of Japanese art and craft. Well-to-do families had long taken the opportunity of social occasions to show off their most sumptuous Chinese tea implements, but this began to change in the 16th century, when aesthetes began to gravitate towards a simpler style.

The popularity of humbly decorated, unpolished, and most significantly Japanese tea implements (what are the Essential Japanese Tea Ceremony Utensils?) began as a trend. It was transformed into a permanent fixture of the Japanese design landscape through the endorsement of political power, in particular military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598) and his tea master Sen Rikyu (1522-1591).

© Ito Sekisui, Red Soil, at Artsy.net

The style of craft which Rikyu favored has come to be known as wabi-sabi. The zen-derived concept, while difficult to translate exactly, refers to a philosophy of imperfection and impermanence. Wabi-sabi can be seen in the preference for understated earth tones over glittering painted colors for example, and for the irregular shapes of hand-molded ceramics over the perfection of wheel-thrown pots.

The popularity of the tea ceremony proved a bracing economic stimulus to Japanese craft, and through the centuries of Edo peace following Rikyu’s time, the wabi-sabi aesthetic spread to the textile, incense, metalware, woodwork and ceramic industries, among others, all eager to supply the finest in Japanese design to their tea practising clients. Read more about Tetsubin Tea Ketttles, Kyusu Teapots and Ikebana Flower Arrangement to learn how tea ceremony artefacts are used. Many of these craft skills are also put to good use in everyday life in Japan’s ingenious bento boxes and traditional dolls.

3. The Art of the Samurai

© Samurai Armor, 18th Century, the Met Museum

People tend to associate Japan with the venerable samurai warrior, but many people may not realize that these skilled fighters were trained in more than just combat.

Samurai (also known as bushi) were the warrior class of premodern Japan — their heyday was during the Edo period (1603-1867). Samurai led their lives according to a carefully crafted code of ethics known as bushido (the way of the warrior).

As the highest caste of the social hierarchy, samurai were expected to be cultured and literate in addition to powerful and deadly. Because they served the wealthy nobility, who highly valued artistic pursuits, samurai warriors also idealized the arts and aspired to become skilled in them.

Samurai were expected to follow both bu and bun – the arts of war and culture. There is even an expression for this lifestyle, bunbu-ryodo, which means literary arts, military arts, both ways.

Miyamoto Musashi by Utagawa Kunisada, 1858

It’s no surprise, then, that many samurai used their wealth and status to become poets, artists, collectors, sponsors, or all the above. Miyamoto Musashi (c. 1584-1645) is a perfect example of this Renaissance man approach — he was a swordsman, strategist, philosopher, painter, and writer in one. He authored the famous Book of Five Rings, which argues that a true warrior makes mastery of many art forms besides that of the sword, such as tea drinking, writing, and painting.

An Actor Posing in Samurai Armor, 1870s

Women could belong to the samurai class as well. Primarily they served as spouses to warriors, but they could also train and fight as warriors themselves. These female fighters were called onna-bugeisha. Female warriors typically only took up arms in times of need, for instance to defend their household during wartime. Yet, some fought full-time and rose to prominence on their own.

Tomoe Gozen by Shitomi Kangetsu, Late 18th Century

One such warrior was Tomoe Gozen (c. 1157-1247), a onna-bugeisha immortalized in The Tale of the Heike. According to the epic, she was beautiful and powerful, possessing the strength of many, “a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god.” Though her existence is attributed to mere legend, warriors were inspired by her valor and she has been the subject of countless kabuki plays and ukiyo-e paintings alike.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, Katana by Osafune Sukesada

Samurai art directly related to combat includes the design and craftsmanship of armor and weapons. Samurai swords, the main tool and symbol of the bushi, are renowned for their craftsmanship to this day, while the descendants of samurai swordsmiths are today producing some of the world’s most highly valued knives. Katana were strong yet flexible, with curved steel blades sporting a single, sharp cutting edge.

18th Century Tsuba, the Met Museum

To separate the handle from the blade was the tsuba, which was evolved from a plain metal disk into the canvas for some of the most intricate metalwork. Family crests, auspicious symbols, and even whole scenes from myth and literature were carved into these elegant accessories. Similarly the netsuke was originally a practical tie to hold a pouch on a belt, but evolved into an elaborately decorated work of art as you will see in these 14 Miniature Japanese Masterpieces!

Kawari Kabuto Helmet, the Met Museum

Samurai armor was equally impressive and intricate. It was expertly crafted by hand and made of materials we may consider opulent, such as lacquer for weather-proofing and leather (and eventually silk lace) to connect the individual scales. Facial armor was also an intricate art in its own right; you can read more at 10 Things You Might Not Know About Traditional Japanese Masks. Even during times of peace, samurai continued to wear or display armor as a symbol of their status.

4. Edo Beauty in Ukiyo-e Prints

Three Famous Beauties, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

The Edo era (1615-1868) enjoyed a long period of extraordinary stability. Edo society was booming and cities expanded on an unprecedented scale. Social classes were strictly enforced. At the top there was the samurai who served the Tokugawa government, then the farmers and the artisans, finally at the bottom of the rank were the merchants.

However, it was often the merchants who benefited the most economically due to their role as distributors and service providers. Together with the artisans, they were known as the chonin (townspeople).

Fujieda: Kichô of the Owariya, Woodblock Print by Keisai Eisen, 1821-23, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

With new prosperity, goods of all kinds flourished. In particular woodblock prints, ukiyo-e, reached their apex in popularity and sophistication.

Ukiyo-e literally means pictures of the floating world. In its Edo context, these stunning woodblock prints highlighted the cultivated urban lifestyle, fashionability and the beauty of ephemeral.

Heron Maiden, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

It was also during this time that printing techniques became highly advanced. The production of woodblock prints was handled by what was then called a ukiyo-e quartet. It included the publisher, who managed the enterprise, the blockcutter, the printer and the artist. By the 1740s, ukiyo-e art prints were already being made in multiple vivid colors. Another important characteristic of these prints is the materials that they use, specifically washi paper, which you can find out more about at All You Need to Know About Washi Paper.

Scene of the Temporary Quarters of the New Yoshiwara, Woodblock Print by Utagawa Kunisada, 1830

One of the most important purposes of ukiyo-e prints was to reflect the stylish lifestyles of the Edo urbanites. Merchants were confined by law to their social status and as a result, those with the means spent their time in pursuit of pleasure and luxury, such as could be found at the Yoshiwara pleasure district.

Display Room in Yoshiwara at Night, by Katsushika Oi, 1840s

Yoshiwara was more than just a brothel; it was a cultural hub for the rich and connected men of the Edo era. This scene vividly demonstrates the fascination with the area, both for those attending, and those who could only watch from the outside. This contrast is made all the more poignant here in this work by the brilliant Katsushika Oi, daughter of the more famous Hokusai. Even today, this incredible artist continues to be pushed to the margins. Read her story in Katsushika Oi: The Hidden Hand of Hokusai’s Daughter.

Somegawa of the Matsubaya, Woodblock Print by Kikugawa Eizan, 1814-17, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The courtesans of Yoshiwara were stunningly portrayed in ukiyo-e prints. Their lavish kimono, hairstyles and make-up were painstakingly brought to life. They were the stars of the Edo, and through these relatively cheap and widely distributed prints their every move was followed religiously by the townspeople in their normal lives.

Beauty, Woodblock Print by Kitagawa Utamaro

These mesmerizing courtesan prints were called bijinga, meaning paintings of beautiful women. The most renowned ukiyo-e artist of this kind is perhaps Kitagawa Utamaro. You can read all about his outstanding art prints in Kitagawa Utamaro: Discover Japanese Beauty Through his Masterpieces.

Cooling off at Shijo, Woodblock Print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1885

Kabuki theater was another popular subject of ukiyo-e in the form of yakusha-e (actor prints). Images of top-billing actors were frequently reproduced, and the prints often captured theatrical scenes with astonishing artistry and detail. You can find out more about Japanese theater in our essential guides to Kabuki, Noh and Bunraku Theater! For more examples of yakusha-e from print artist Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, you can read The Stories Behind the 100 Aspects of the Moon.

Pleasure Boat, Woodblock Print by Toyohara Chikanobu, 1880s-90s

One of the more famous ukiyo-e artists of the time Toyohara Chikanobu, has for some reason become somewhat obscure outside of Japan today. He remains, however, one of the most collected woodblock artists domestically. To enjoy his sensational bijinga prints, take a look at Who Was Chikanobu?

5. Traditional Japanese Architecture

Gion Shirakawa Canal in Kyoto

Japanese Architecture is often noted for its display of extreme oppositions and contradictions, whether it’s the sprawling grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo or the intimate scale of the traditional Japanese teahouse. Perhaps most widely recognized as distinctly Japanese is the residential architecture of the Edo period, of which many examples survive today.

© Jonathan Miller, Traditional Japanese Architecture

Japan is known for having some of the oldest wooden buildings in the world. The use of wood as a source material in Japanese housing is widespread. This approach embodied both a spiritual and practical application. Due to Japan’s frequent natural disasters, like earthquakes and typhoons, builders sought to use wood as it was resistant to push and pull. In contrast to Western houses, wooden Japanese structures were never painted over, leaving the grain visible as a way of showing respect for its natural value.

© 2019 Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

One element of the traditional Japanese house that remains popular today is the unique flooring of the tatami mats. Historically, wealthier families afforded tightly woven tatami made of rush, while poorer families used mats made of straw. As any visitor to Japan knows, you are expected to remove your shoes before walking on Japanese tatami mat, or indeed in any Japanese home whatever the flooring! Tatami are ideal for Japan’s humid climate, as they can absorb water in the air which will efficiently evaporate on a dry day.

© M Murakami / Creative Commons, Shoji Lattice

The delicate wooden or bamboo framework of shoji, which are screens or room dividers, are both functional and artistic in nature. The elegance of this traditional Japanese housing element is found in the light that shines through its translucent paper (washi), creating atmospheric shadows within a home. Some shoji are painted on, and others maintain their traditional white facade. You can learn more about shoji screens and the elaborate kumiko woodwork that is used to make them.

© 2019 Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

From the outside of a Edo-era Japanese home, you can usually notice that it is raised up off the ground in an effort to prevent rain damage. Additionally, instead of using nails, Japanese wooden structures were built with a supporting block system called tokyo, in which the pieces fit together naturally.

© GoTokyo.org, Hamarikyu

Surrounding the outside of a traditional Japanese home is a porch-like veranda called an engawa. Though part of the home, the engawa exists as a bridge, connecting the inside and the outside worlds. The relationship between shoji and engawa is poetic and playful, shoji and fusama maintaining the roles of opening and closing the house to light, shadows, and air from the outside. As seen in Hamarikyu gardens in Tokyo, the teahouse engawa plays an important role in the relationship between indoor and outdoor. To get a better sense of the layout of a traditional Japanese home take a tour Inside 5 Timeless Traditional Japanese Houses.

© All Japan Real Estate Association, Kawagoe

A look at the fire resistant structures known as kura-zukuri in the Kawagoe district brings one back to the Edo period. Also known as “Little Edo,” Kawagoe was well known for its prosperous trade. Unfortunately, the small town endured devastating fires and ruin in the 1800’s. Thus began its rebuilding with clay-walled warehouses to prevent further damage.

Shirakawa-go, Gifu

The famous gassho-zukuri farmhouses found in Shirakawa-go are excellent examples of traditional Japanese architecture. Literally translating to “Built like hands in prayer,” gassho-zukuri is a thatched roof architectural style developed to tolerate heavy snowfall in winter. The nature of the space created with the A-frame technique allows for a large attic area for raising silkworms. The gassho-zukuri farmhouses that extend from Gifu to Toyama Prefecture have now become a UNESCO world heritage site, and are certainly one of the 10 Best Towns to Enjoy the Winter Snow in Japan.

© Pacific1688 / Creative Commons, Katsura Imperial Villa

As if withdrawing from the simplistic and austere garden design of the Momoyama period that preceded it, the Edo period brought with it a sense of garden extravagance for those in the upper echelons of society. “Strolling gardens,” gardens made for long, peaceful, even meditative walks, were built with artificial hills, ponds, and an abundance of natural elements such as plants, and bamboo. Although these strolling gardens were initially constructed for feudal lords’ private homes, the Meiji period shifted the boundary from private to public. This can be seen in Kyoto at the Katsura Imperial Villa. A garden made with the mentality to observe the space not inhabit it. If you’re interested, take a look at our travel recommendations to experience the unique beauty of Japanese garden design whether you’re in Tokyo or America.

6. The Rise of Japanese Ceramics

Small Dish with Cherry Blossoms, the Met Museum

The beauty and splendor of Japanese ceramics is renowned worldwide, and there are a multitude of world-class ceramic styles (see our A-Z Guide to Japanese Ceramics). Yet it is little known that the beloved pottery that captivated the world in the 1600s came from a humble southern town called Arita.

As in many societies, Japanese ceramics date back to the neolithic era. The earliest pieces of Japanese art come from the Jomon Period (circa 14,000 to 300 BCE), which was actually named for the corded rope used to imprint designs onto earthenware clay (jomon can be translated as rope-marked).

© Tjabeljan / Creative Commons, Okawachiyama, Imari

The production of what are considered modern ceramics began during the Edo period, the time of Tokugawa rule. This era is often remembered for the isolationist policies of the Tokugawa shogunate – foreign trade and travel was largely banned, leaving Japan cut off from the rest of the world.

Yet, trade did manage to thrive within certain limits. The Dutch East India Trading Company (or VOC) was allowed to trade in Japan, but only at certain designated ports in Nagasaki. The most notable of these was Dejima, an artificial island created to segregate foreign traders from Japanese residents.

© Japan Objects, Touzan Shrine, Arita

Korean potters were brought as slaves to Japan following Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s (1537-1598) 1592 invasion of the peninsula. One such slave was Yi Sam-pyeong (d. 1655). It is said he discovered a natural source of clay in the mountains near Arita, no too far from Nagasaki, which inspired him to teach his art to the locals. Though elements of the story are disputed by historians, the accepted narrative is Yi Sam-pyeong is the father of Arita pottery. There is even a shrine in Arita dedicated to his memory. Thus, the Japanese porcelain industry was born.

Kakiemon Plate, Late 17th Century

Whereas traditional Chinese porcelain (which previously dominated international trade) was characterized by simple blue and white patterns, Aritaware was brightly-colored due to a pioneering overglazing technique. This style is called Kakiemon after its creator, a potter named Sakaida Kakiemon (1615-1653).

This distinct pottery also became known as Imari by Westerners. Imari was the port from which Arita ware was shipped to other parts of the world via Dejima. Read more about the modern day region at 6 Best Japanese Ceramic Towns You Should Visit.

© Arita Porcelain Lab, Gallery Plate

Arita/Imari pottery was exported to Europe in large quantities by the VOC. The Dutch initially traded pottery from China, but nationwide wars and rebellions lead to the destruction of kilns and halting of trade. The Dutch turned to Japan, and amazingly the Arita kilns were able to export enormous quantities of porcelain to Europe and Asia between the second half of the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century. Learn more about Arita and its future by reading The Future of Japanese Pottery: Arita Porcelain Lab.

Japanese Plate Made for Export, 1770, the Met Museum

The VOC also influenced Japanese art another way. The mere presence of the Dutch in Dejima, one of the earliest forign settlements in Japan, had an effect on local artists. Depictions of daily life on the island featured on prints bought as souvenirs by Japanese tourists. Images of the Dutch were painted on the very same porcelain they made a living off of. Paintings and books brought from Holland inspired many Japanese artists in turn, introducing them to new ideas and techniques.

7. Japanese Art: The Splendor of Meiji

© Ito Shinsui, Shimbashi Station, 1942

The Meiji Restoration in 1868 marked a turning point in Japanese history. Gone with the feudal past and military rulers, Japan at this time was firmly marching towards modernization and westernization under the leadership of Emperor Meiji. The Meiji and Taisho era (1868-1926) was distinctively different from what had come before in all aspects. The nation was in a constant state of flux, pulling between the West and the new Japan.

Uchikake (Outer Kimono), 1870-90, Victoria & Albert Museum

In the arts, there were significant technological and stylistic developments, thanks to Japan’s newly enthusiastic engagement with the world in the form of international exhibitions and expositions.

It was in the textile industry where production methods first began to modernize. In the 1860s, Kyoto’s Nishjin – the premier center of the kimono industry - sent delegates to Europe to bring back the jacquard loom that transformed weaving processes.

© Tatsumura, Black and Gold Obi Belt

Woven textiles fashioned in Kyoto’s Nishijin district are known as Nishijin-ori, or Nishijin textiles. Works of Nishijin-ori tend to feature vibrantly dyed silks interwoven with lavish gold and silver threads into complex, artistic patterns. Nishijin-ori constitutes more than just kimono and obi (kimono sashes) manufacturing — other products include festival float decorations and elaborate Noh costumes.

Silk Weaving by Kitagawa Utamaro I, 1797

Japanese silk weaving was first brought to Kyoto by the Yasushi family, who immigrated to Japan from China sometime in the 5th or 6th century and taught the art to the local people.

Though the Nishijin weaving industry predates Kyoto’s role as the seat of the Imperial family, it wasn’t until after Kyoto officially became the capital of Japan that Nishijin-ori production took off. The opulence of courtly life practically demanded flamboyant, high-quality dress, so a special bureau was created and put in charge of textile manufacturing for the court. However, by the end of the Heian period (794–1185), the time when the Imperial court was at its peak, court-sanctioned fabric production inevitably declined.

© Tatsumura, Uchikake Kimono

Nishijin-ori managed to continue as a private industry and was eventually able to thrive on its own. The peaceful and prosperous Edo period was the golden age of Nishijin textiles, but after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Nishijin-ori makers lost their feudal patrons due to government reform. With no more shogun and samurai around to support them, they were left on the brink of extinction.

© Tatsumura, Silk Weaving

Rather than abandon production, the weavers of Nishijin took steps towards creating more modernized textile production methods.

In 1872, Nishijin sent an envoy of students to Lyon, France to study new textile technologies. As mentioned above, these students arranged for various types of modern looms, including the French jacquard loom and English flying shuttle loom, to be imported to Japan. With this new knowledge of industrial processes, Japanese companies were quick to take up the challenge of modernising the industry.

© Tatsumura, White and Gold Obi Belt

Tatsumura Art Textiles is one such company. Established in 1894, the Tatsumura family has been artfully weaving luxurious textiles for generations. The company has a stunning client roster, including Emperor Hirohito and Christian Dior, which goes to show how respected the Nishijin-ori industry remains.

The designs of founder Heizo Tatsumura transformed the Japanese textile market, so much so that his patented works were quickly infringed upon by competitors. Tatsumura, however, turned what was sure to be a disaster into an opportunity: after ten years of studying classic designs and patterns that came to Japan via the Silk Road some 1300 years ago, he created one-of-a kind textiles for kimono and obi and items for tea ceremony.

© Tatsumura, Red Obi Belt

Throughout his lifetime, Tatsumura was responsible for creating reproductions and restoring priceless tapestries from a number of notable historic buildings in Japan, including Shosoin Repository (the treasure house of Todaiji temple) as well as Horyuji Temple, the world’s largest wooden building. It is fitting that both of these buildings are located in Nara, as it was established as Japan’s first permanent capital in 710.

Here lies the success of Tatsumura Textiles - a seamless synergy of Eastern dyeing methods and Western weaving technology forged with the concept of onko chishin (“learning the past in order to create something new”).

Dragon Pot, 19th century, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In the field of metalwork, Meiji-era artisans were forced to find new suitable endeavours quickly. The abolition of the samurai class and the prohibition of sword-carrying in 1876 meant that their industry collapsed almost overnight.

But many did find other outlets for their talents, and with exceptional success, as can be seen from the superb craftsmanship of this dragon-themed jar. The silk wrapper on this jar is intricately carved, and particularly fine work considering it is not actually silk, but metal.

© Uemura Shoen, Woman Waiting for the Moon to Rise, Nihonga Painting, 1944, Adachi Museum of Art

Meiji painters eagerly sought novel ways to reflect the spirit of the new Japan. Students, scholars and artists often traveled to Europe or America to bring back western styles known in Japan as yōga (western paintings). But for others, the Japanese way could only be captured by building on centuries of national heritage.

© Tetsu Katsuda, Evening, 1934, Adachi Museum of Art

These elegant Japanese art style is known as nihonga (Japanese painting), which are perhaps not widely known internationally, but were created by some of the best Japanese artists to date. You can get a taste of this remarkable Japanese style of painting from our Concise Guide to Nihonga, or read Japan Objects' exclusive interview with Rieko Morita, who is one of the best-known and respected Nihonga artists working today. You can also learn more about the birth of the Nihonga movement in The Secret Hideaway of Japan’s Best Nihonga Artists.

Lake Kawaguchi, Woodblock Print by Tsuchiya Koitsu

Perhaps the major social influence of the Meiji and Taisho periods of the history of Japanese art was state-led nationalism. This patriotic sentiment greatly influenced the arts of the time too. Tsuchiya Koitsu’s Mount Fuji woodblock print is an interesting example of this. Take a look at The Meaning of Koitsu’s Prints of Mt Fuji to read more.

The Meiji era’s unrelenting modernization was keenly felt by many artists and artisans. The desire for a more ethical and inclusive way of working took hold through the establishment of Mingei, or the Japanese Folk Craft Movement. The aim was to revive struggling vernacular craft industries through formal design study, similar to the British Arts and Crafts Movement of the late 19th century.

© Okamura Kichiemon, Sake, Woodblock Print

This charming print is an example of the unique Japanese rural style of Mingei. It spells out the kanji character 酒, meaning sake or alcohol, using the ceramic jars and small cups in which sake is usually served. Print master Okamura Kichiemon was fascinated by the everyday objects of Japanese life, such as the tableware illustrated here, and was the author of many books about Mingei.

8. Modern Japanese Architecture

© Alex Roman, Chichu Art Museum, Naoshima, from his book From Bits to the Lens

After the devastation of World War II, Japanese Architects took the lead in the reconstruction and reshaping of the country. Influenced by their circumstances and eager to rebuild, Architects sought not only to stabilize but to innovate; to distill a uniquely Japanese practice in creating spaces.

© Wiiii / Creative Commons, The Shizuoka Press and Broadcasting Center in Tokyo

The post-war architectural movement aptly named Metabolism was an initiative that aimed to instill living, breathing (almost biological) mechanisms and structures at the heart of a city that would change with and for the inhabitants of a metropolis. Metabolism was a movement in response to the masses that were moving to the inner cities and to the increasing economic wealth Japan entertained during the Bubble Era.

© Tom Blachford, The Nakagin Capsule Building. From Nihon Noir

One of the most famous creatiions from this time period is the Nakagin Capsule Building in Ginza made by Kisho Kurokawa in 1972, and here beautiful captured by photographer Tom Blachford in his collection Nihon Noir. The apartment business complex is made up of small removable furnished apartment rooms, or cells, that are individually installed and connected. The design was intended to be modern even futuristic by meeting the practical needs of a lone, hardworking salaryman of the time. Most notable about Metabolism was its intention to anticipate the needs or not yet known needs of the future inhibitor of a space. Now a monument for artists, architects and the occasional curious passerby, Nakagin has become a symbol of the movement that was. However, its dilapidated state has continuously brought up the discussion of demolition, a fate that has yet to be determined.

© Nippon.com, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

In similar hopeful and anticipatory fashion, the famous Japanese architect, Kenzo Tenge, designed the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. The park was built shortly after World War II and the American occupation which ended in about 1952. Consequently, the design embodies the complex emotions that surfaced regarding western influence, nationalism, and a move towards maintaining elements of traditional Japanese architecture. What began as a project to represent what is modern and international morphed into Tenge’s simultaneous appreciation of the traditional. This resulted in a redesign of the redesign. It is important, especially to Tenge, to distinguish Japanese design from western influence.

© Naoya Hatakeyama, Sendai Mediatheque

Contemporary Japanese architecture can be seen in Japan today in Toyo Ito’s Sendai Mediatheque which was built in 2001, here captured by photographer Naoya Hatakeyama. The structure is a prime example of the shift towards free expression in modern Japanese architecture. The open structure and the use of tubes in the cultural media center invites the community to the space, and the space to the community. “It all started with the image of something floating in an aquarium.” Says Toyo Ito in a video interview by Richard Copans. The eco-friendly building is visually compelling and allows for a plethora of spacial activity within the structure, which consists of gallery space, a cinema, libraries, a cafe, and more. True to Japanese aesthetic and sentiment, the space can notably change with the lighting of the seasons, the trees from the street visible from several vantage points inside the building.

© Benesse Art Site Naoshima, Chichu Museum

Perhaps one of the most pervasive and famous contemporary Japanese architects is none other than Tadao Ando. Known for his experiments with concrete, and for the way his design challenges how we anticipate inhabiting a space, Ando was one of the artists who helped save Naoshima island in the 1980’s from population decline. His work, Benesse House Museum, played with the relationship between architecture, nature, and art. Ando is a self-taught architect, who can be identified as an auteur. As if recalling Junichiro Tanizaki’s essay In Praise of Shadows, a signature Ando design plays with shadows, light, and patterns. He says his work reflects the ‘intimate relations between material and form, and between volume and human life.’ For a better view of his work, check out these 10 Iconic Tadao Ando Buildings You Should Visit.

© Ryue Nishizawa, Moriyama House

In the spirit of minimalistic simplicity and communal living, Ryue Nishizawa designed Moriyama House, which was completed in 2005. This design is a metaphysical representation of the relationship between an inhabitant and their community, or rather, coexistence with self and others. Designing a house for a client is personal and sensitive, making the role of architect both challenging and exciting. How does one design, and yet meet or anticipate the needs of a human being? In Moriyama House, Nishizawa designed separate, right angled houses, or ‘volumes,’ and arranged them in a unique cluster. The effect resulted in some units containing a room with a single function, and other ‘mini-houses’ that contain a more completed design. Moriyama himself rents out the ‘mini-houses’ and thus a small community based on this Japanese minimalism was born, blurring the line between private and public, shared and separate, among other binaries in both architecture and daily life.

© Daici Ano, Ginzan Onsen Fujiya

One of the most in vogue architects of this moment of contemporary Japanese architecture is Kengo Kuma, whose relationship to nature is notable in most of his work. As an architect he traverses the river between designer and craftsman, with intent focus on material, and how it’s made. His essay, Studies in Organic, speaks of the importance of the relationship between craftsman and architect. Through reinventing traditional architecture, the contemporary architect is applying aspects of nature to a modern world and creating sustainable structures. In his renovated work, Fujiya Ryokan, one can see how a 100 year old building was taken care of and refined. Seemingly simple at first glance, a closer and more careful observation of his designs could reveal a deeper and more meaningful understanding of a craftsman at work.

9. The Japanese Art of Craftsmanship

© Pray for Kumamoto, Brooch by Mariko Kumioka

Japan’s frenetic modernization after World War II brought increased prosperity to many, but in the art world, fears began to rise that Japanese traditional craft skills were being drowned under the incoming wave of western cultural mores.

In response the government enacted a series of laws to encourage and support the arts including the designation of important cultural properties, and the informal title of Living National Treasures for master artisans, who could carry traditional skills into the future.

© Joan B Mirviss Gallery, Vase by Matsui Kosei

Matsui Kosei (1927-2003) was one such national treasure. By looking back at previously extinct craft skills, Kosei was able to develop the neriage technique to fashion such intricate and colorful creations as this incredible striated vase. For more ceramic masters check out These Phenomenal Japanese Ceramics, or explore Japan's 11 Best Female Ceramic Artists.

© Kubota Itchiku, Mount Fuji and Burning Clouds Kimono

Forgotten techniques were the inspiration for artist Kubota Itchiku as well. Through his careful experimentation with a 700 year old shibori dyeing style, tsujigahana, he turned a usually understated item into the canvas for his passionate and emotional art, such as this piece, Mount Fuji and Burning Clouds.

For a more detailed introduction to shibori visit 5 Things You Should Know About Japanese Shibori Dyeing, or learn more about Japan’s traditional indigo dye. In the world of Japanese kimono, yuzen dyeing is particularly intricate and refined, embodying the unique category of wearable art! Check out What You Should Know About Yuzen Kimono. There are also many other extraordinary kimono designs for you to explore in Kimono Designs: 9 Must-See Japanese Masterpieces.

© Yukito Nishinaka, Yobitsugi Glass Jar

Glass, by contrast, was not commonly used in Japan before the Meiji restoration. However, with the spread of western-style housing, and windows, artists were quick to discover the potential of such a versatile material. Yukito Nishinaka is one such craftsman working today. Inspired by the Japanese craft objects of the past, Nishinaka aims to reinterpret such objects as teaware and garden ornaments, all through the medium of glass. You can see more art from Nishinaka and his peers, at Glass Artists to Shatter Your Preconceptions.

© Juliet Sheath, Bamboo and Box Brooch by Mariko Sumioka

Art Jewelry is another area that, although not native to Japan in its modern form, is able to draw on the country’s rich cultural heritage to produce unique works of art. Mariko Sumioka, for example, finds inspiration in the architectural language of Japan. She sees the aesthetic value not only in the homes and temples that can be found here, but also in the individual components of the structures: bamboo, lacquer, ceramics, tiles and other traditional craft and building materials. Get to know some of the other craftspeople bringing Japanese art history to life at How Japanese Jewelry Design Draws Inspiration from Traditional Art.

10. The Future of Japanese Contemporary Art

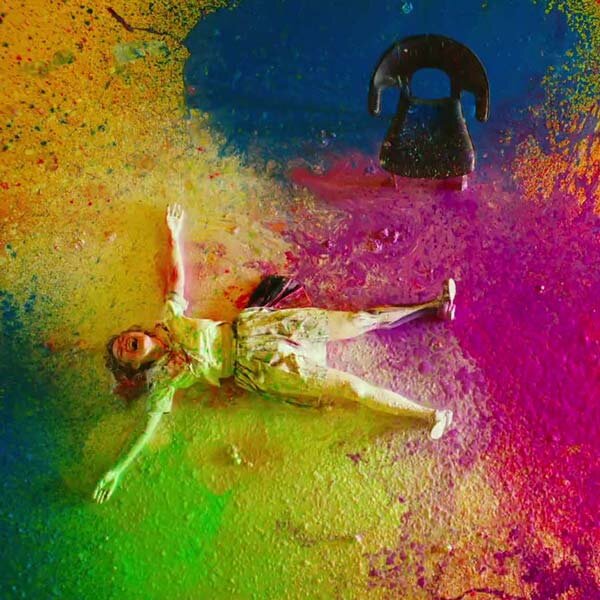

© Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Mirrored Room, 1965

Japanese contemporary art in the 21st century reflects its creators’ conscious efforts towards innovation and experimentation. Pioneering artists today move swiftly between artistic mediums to express their uncompromising visions. From manga and fashion, to digital sculpture and photography, the accepted disciplinary boundaries are being broken down to make new ways for artistic and social autonomy.

Artistic autonomy rings especially true for the emergence of new Japanese women artists. There are an unprecedented number of professional women working in the creative fields, and established artists such as Yayoi Kusama have paved the way for young female artists to thrive. You can get to know some of these talented women in Female Artists You Should Know, Famous Female Painters, and Japan's Most Popular Female Manga Artists! You can also visit Kusama’s public works in person, wherever you are in the world: Where to See Yayoi Kusama’s Art.

This silver wreath by Wales-based artist Junko Mori is an example of stunning craftsmanship, where unyielding metal is cast as tender spring petals.

© Junko Mori, Silver Poetry; Spring Fever Ring, at Adrian Sassoon

This one-of-kind piece entitled 'Silver Poetry; Spring Fever Ring' is an appropriate introduction to her instinctive making process: ‘No piece is individually planned but becomes fully formed within the making and thinking process. Repeating little accidents, like a mutation of cells, the final accumulation of units emerges within this process of evolution,’ says Mori.

Similar to Rakuware by a tea master craftsman, Mori’s work embodies that rare quality where accidents are celebrated for their uncontrollable beauty.

© Takahiro Iwasaki, Duct Tape Scupture, Geoeye (Victoria Peak), courtesy of Urano

Takahiro Iwasaki’s Out of Disorder series is a fascinating example of cutting-edge experimentation, in which he uses discarded everyday objects to create incredibly detailed miniature cityscapes. You can read about his work in The Story of Takahiro Iwasaki's Radical Sculptures.

© Takashi Murakami, Flower Matango Sculpture at the Palace of Versailles, 2010

Rule-breaking convictions are thoroughly evident in many of the works of Takashi Murakami. The sight of his sculpture Flower Matango in the Palace of Versailles is an ideal illustration of the thrilling clash between traditional art and pop culture. By presenting a new hybrid of these influences, Murakami takes his place as one of the most thought-provoking Japanese artists working today. You can check out Iconic Japanese Contemporary Artworks to discover more! If you’re in Tokyo, you can also visit the country’s first Digital Art Museum showcasing the works of art collective teamLab. Check out our exclusive interview here.

It’s not just the art superstars that are worthy of attention, however, Japan is overflowing with undiscovered talent like these 10 ‘Outsider’ artists!

© Masayo Fukuda, Umidako

Often centuries-old traditions provide the tools for contemporary artists to demonstrate their creative skills. Here you can see how Masayo Fukuda has developed new avenues for the technique of kirie, or Japanese paper cutting. Using one single sheet of washi paper, she has painstakingly carved an elaborate and beautiful marine creature that seems to come to life in your hands! Find out more about these 5 Kirie Japanese Paper-Cutting Artists You Should Know.

© Chiharu Shiota, State of Being (Children’s Dress), 2013

Berlin-based artist Chiharu Shiota has a distinctly pertinent vision of artistic innovation. She creates large-scale installations exploring the vocabularies of anxiety and remembrance. State of Being, for example, is a stunning portrait of the powerful connections between people and their belongings. By encasing everyday things, like a child’s dress, in infinite webs of red yarn, she transforms ordinary objects into evocative personal memories.

Do you have any questions about Japanese art or Japanese history? Let us know in the comments below, and we'll get you the answers!

ART | October 6, 2023